- How to study the changing climate at ground-based observatories

- How the astronomical observations are affected

- What can be done about it

With nearly 20 telescopes currently in operation, ESO’s observatories play a key role in the exploration of the Universe. Located in the remote Atacama Desert of Chile, the observatories have pristine and unmatched views of the skies. But even in these remote sites the effects of climate change are being felt, which could make ground-based observing of the Universe trickier in the future. In some aspects, it already is.

With upcoming ground-based telescopes boasting mirrors over 30 metres wide, the world of astronomy is rapidly changing; however, with human-made greenhouse gases being released into the Earth’s atmosphere, so is the climate. Rising global temperatures and the climate changes they bring have, in the past decades, manifested themselves in record-breaking heat waves, warmer oceans, melting glaciers and an increase in the intensity of forest fires, to mention but a few.

As astronomers, we see the effect of greenhouse gases in the atmospheres of other planets — Venus is an inhospitable example. We recognise that there is no Planet B, and even if there was, we could not reach it. At ESO, we recognise the importance of sustainability in our activities, and we are addressing our own environmental impact. After all, the devastating effects of climate change impact the whole world, as we are all too aware.

It is not well understood, though, how climate change might affect science and, more specifically for ESO, astronomy. And if global warming is going to have an impact, what can we do about it?

Where to build your telescope?

There are many aspects to consider when scoping out sites for next-generation telescopes, such as geopolitics, cost, geology, ecology and local culture, but an important factor is climate, as this will dictate the quality of astronomical observations.

“If we are mainly caring about optical astronomy, then the fraction of clouds over a particular year is important for that project, right?” asks Angel Otarola, Atmosphere Scientist at ESO. “If we are thinking about millimetre [wavelength] radio astronomy, then we need to look for sites where it is absolutely dry in order to minimise absorption by water vapour in the atmosphere.”

The skies over astronomical sites need to have little to no light pollution, low humidity and, ideally, a stable atmosphere. Turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere can distort starlight and blur astronomical observations, even in otherwise pristine conditions. It’s a bit like trying to focus on a coin sitting on the bottom of a swimming pool. As the water ripples on the surface, your view of the coin gets distorted. If you tried to take a photo of the coin, particularly with a long exposure, it would end up blurry. The atmosphere, which behaves just like any other fluid, distorts the distant light of astronomical objects in a similar way. This effect, called “seeing” by astronomers, is what causes the twinkling of stars as seen from the Earth.

The most natural solution to problems such as turbulence or water vapour is to select high-altitude sites to observe from, minimising the thickness of the atmosphere above the telescopes.

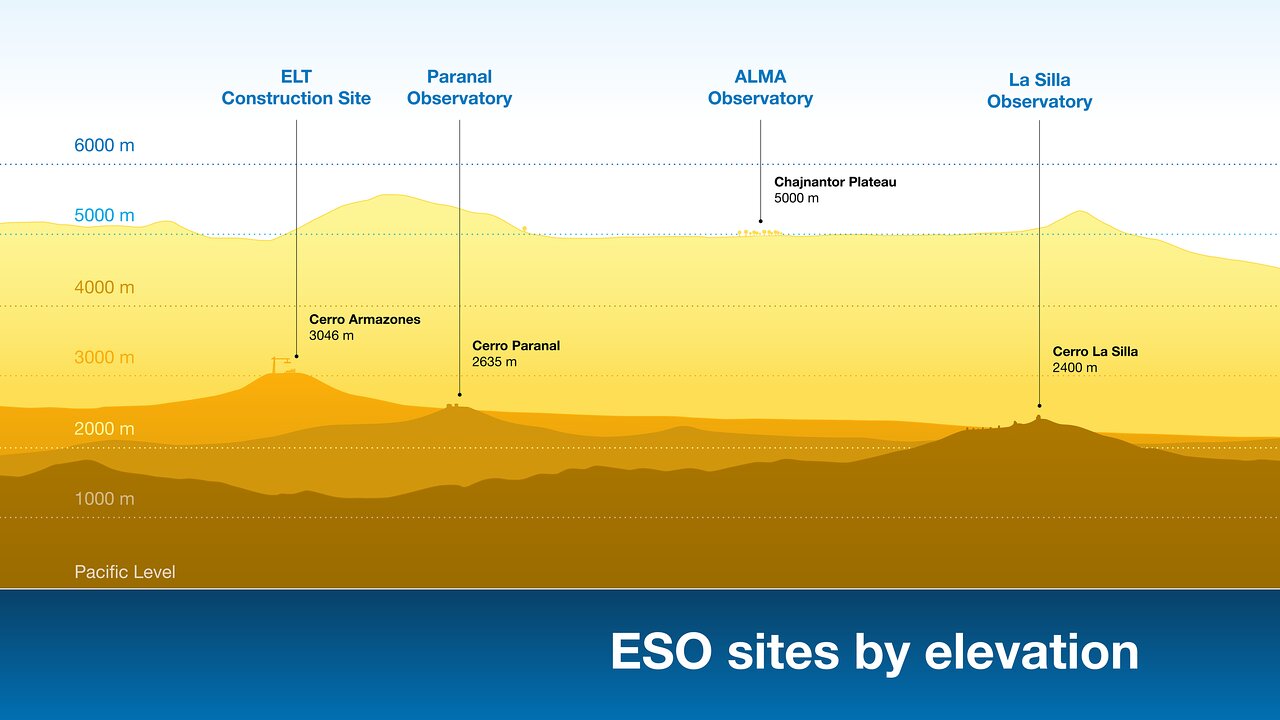

In the 1950s, the La Silla site, at 2400 metres above sea level near the Atacama Desert in Chile, was found to be such a place, and it became home to ESO’s first observatory. By the end of the 80s, site testing had picked up again to find a home for the Very Large Telescope (VLT), which ended up at Cerro Paranal, 2635 metres above sea level, further north in the Atacama Desert.

The next major project, scoped out in 1995, was the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). ALMA demanded especially high and dry conditions, because at millimetre wavelengths, water vapour in the atmosphere absorbs signals from space. The Chajnantor Plateau at 5000 metres fit the bill.

This extensive site testing in the Atacama Desert helped out when it came to placing what will be the world’s biggest eye on the sky, the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT). Cerro Armazones, near Paranal, was an easy decision, thanks to its outstanding weather conditions and the existing infrastructure.

The Atacama Desert hosts some of the best sites for astronomical observation on the planet. But how severe are the local climate changes in these locations?

How to study climate change at an observatory

“One day whilst working at Paranal, I realised that it really is a unique site, because there are not many sites that are equipped with so many meteorological sensors,” says Julien Milli, an astronomer at the Institute for Planetary Sciences and Astrophysics in Grenoble who used to work at ESO’s Paranal Observatory. Julien’s research focuses on detecting exoplanets using highly sensitive imaging techniques; he needs the most pristine skies in the world to access the delicate light from faraway, cold planets.

“When I was in Paranal it was part of my duties to monitor all the sensors that check the environmental conditions. This includes the temperature, pressure, humidity, but also astronomy specific sensors such as the seeing monitor,” Julien says. “It really is a goldmine! There is all this historical data available to us, for astronomy, but also from a climate perspective, starting from the beginning of the site testing in the late 80s.”

Site testing involves the same monitoring systems as are used for ongoing observing each night. Importantly, this data has been preserved and provides a long-term baseline for the environmental conditions at a site. “One thing we have done at ESO is that a database has been put in place, already many years ago, for what we call the astronomical site monitoring system, and we try to preserve these measurements,” Angel explains.

Alongside Julien, Faustine Cantalloube, an astronomer at the Marseille Astrophysics Laboratory, is an exoplanet hunter. “We both tried to understand what limits the observations and why we weren’t discovering as many planets as [we wanted] to,” Faustine says, explaining that as they were doing image processing they “noticed a flare that showed up in the images, blocking the view of the planets. From talking with one of the support astronomers at Paranal about it, we realised the connection to it being an El Niño year, and that the flare was caused by the intense winds.”

El Niño is an irregular climate phenomenon characterised by the warming of sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean towards the west coast of the Americas. This warming disrupts normal weather patterns, leading to varied impacts such as increased rainfall in some regions and warmer and dryer conditions in others. Its counterpart, La Niña, is marked by cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures in the same Pacific region, influencing global weather patterns with effects opposite to those of El Niño. Typically, an episode of either El Niño or La Niña lasts for months to a year, and the period between El Niño and La Niña events ranges from 2 to 7 years.

This discovery triggered further research using the vast set of historical data in ESO’s monitoring system. Julien says, “I thought we should use this database to see if we can find hints of climate change and maybe raise awareness among not only astronomers but the public as well.”

And in many regards they were lucky with the goldmine of data at Paranal. Faustine explains that in climatology, trends have to span more than 30 years to be considered reliable. “And it turns out that when we started the study, [there] were exactly 30 years of data collected”. Combining the three decades of data with atmospheric models, Faustine and Julien led a paper that was published in Nature in 2020, the first indepth study of climate change at an astronomical observatory. So, what did they find?

How Paranal is affected by climate change

“When the [telescope] domes open for the night, we don’t want to have a temperature difference between the air inside the dome and the air outdoors,” Julien says. If the telescope’s mirrors are warmer than the air temperature outdoors, heat waves ripple above them like those above a desert highway on a hot summer's day. This in turn causes “dome seeing”, resulting in a blurring similar to the atmospheric seeing.

To get the mirrors in equilibrium with the outside air temperature, at the end of every night, a prediction of the temperature at the following sunset is made and is set as the target temperature for the telescope air conditioning system to maintain during the day. When this temperature system within the VLT domes was constructed 30 years ago, it was only able to maintain a temperature of up to 16 degrees Celsius. “But on some warm summer days, which are now more and more common, the temperature at sunset is actually above 16 degrees,” Julien says.

Indeed, the team found that the temperature at Paranal has risen by 1.5 degrees over 30 years — more than the global average. This has a significant effect on the conditions within the domes of the telescopes as well as outside.

The turbulence in the atmosphere from the ground up to around 1 km in the air is also heavily affected by the changing temperature gradients and winds, increasing the close-to-the-ground seeing. This makes astronomical observations much more tricky, and the worst affected fields are the most high-precision ones, requiring the most pristine skies. Detecting exoplanets, as Julien and Faustine do, is one such field, but there are plenty of others affected too.

As well as an increase in temperature, they noted that roughly twice a year Paranal experiences high humidity, brought by winds from the Amazon forest. “Those events usually last 2-3 days, and now we don't know what's going to happen with climate change,” Faustine says. “We don't know if those events are going to be more frequent, if they are going to be longer or disappear completely.”

That’s Paranal… What about other ESO sites in Chile?

Julien and Faustine’s work is only the first dedicated study connecting climate change to an astronomical observing site. Each site, however, is unique.

This prompted Julia Seidel, an ESO astronomer in Chile with a background in climate science, to team up with Angel to look at climate trends from a different perspective. Using similar historical data, all three ESO observing sites in the Atacama Desert were studied to see if long-term climate patterns, such as El Niño, or climate change trends are impacting the observing conditions. Their results were published in Atmosphere earlier in 2023.

They found an increase in temperature across all sites of about 0.2°C per decade or more, consistent with anthropogenic climate change. The exact increase varied from site to site, with Chajnantor experiencing the greatest increase in temperature. Warming tends to happen much quicker at higher altitudes, and at about 5000 metres elevation, Chajnantor is twice as high as the other observing sites.

It is not only the mean temperature that matters, however. In El Niño phases, they observed more days near the historical maximum temperature. This correlation reversed for the humidity at site; in these phases the surface level humidity was lower. In La Niña, conversely, there were cooler days and more wet periods. Despite the fluctuating water vapour, no overall increase in humidity was recorded over the years for which they had data [1].

Typically, the atmospheric temperature and humidity are monitored for how they affect the quality of an image. Increased humidity also has severe impacts for the instrumentation, making it hard to calibrate infrared instruments in humid conditions.

These initial trends matched their expectations compared with global warming trends. An interesting and astronomically important result that Julia and Angel observed was that there was no increase in seeing over time — the turbulence varies, especially during La Niña, but overall has not changed. “In a complex terrain area, there is always a relatively strong turbulence layer near the surface. And we don't see, at this point, a modification in the strength of that turbulence layer due to climate effects,” Angel says.

While Faustine and Julien found an increase in seeing at Paranal, Julia and Angel’s study using all available data at ESO’s sites found this to not be the case. “The quality of seeing being stable is quite an important fact to have. And I think this is one of the most important outcomes of this paper from the data that we have at this moment in time,” Julia emphasises.

What can be done?

Aside from site selection, technology is able to compensate for some atmospheric interference. One solution is to use adaptive optics, an advanced technology that corrects for the turbulence in the atmosphere by using a mirror that can change its shape at millisecond speeds to adjust the light that reaches the telescope and compensate for the image distortion.

As a former adaptive optics scientist at Paranal, Julien assures us that the adaptive optics systems in their current state are sophisticated enough to deal with some increased turbulence.

Predicting the weather is also key at the observatories. Julien stresses that implementing better weather forecasting will be extremely important to make the most of the time available at the telescopes by strategically designating more humid and turbulent weather to the types of observations that can cope with it better.

With years of climate data already in hand, there is some predictive power for which seasons would be better for observing and which have poorer weather and could be used for maintenance. ESO plans its observations in half-year intervals, accommodating for the conditions and constraints the scientists include in their proposals. Different observations may require lower water vapour or a more stable atmosphere, while others are more flexible for the conditions. This way, priorities can be set to reduce the amount of time the telescope is idle during bad weather.

Now, with the additional knowledge about the impacts of El Niño and La Niña through Julia and Angel’s work, idle time can be reduced even further. “One of the interesting aspects of our work is that having this indicator of whether we are in El Niño or La Niña gives us a little bit of a better grip on when the good periods are to prioritise challenging infrared programmes,” Julia explains. For example, in La Niña, where wetter conditions are more likely, observations that can handle a higher level of water vapour can be planned for.

Julien adds that there are already plans to put a system in place that can implement machine learning techniques to make better local weather forecasts. “I'm really looking forward to seeing how reliable it is, and if we can use it to schedule the observations, both for the VLT and the ELT.”

At this point, you may be wondering, if climate change is affecting these observatories, why not just put all telescopes in space?

There are pros and cons to both space- and ground-based observatories, and together they complement each other very well. “On the ground, you can afford to have really huge telescopes, and from that you gain both in resolution and sensitivity, even though you lose a little bit of sensitivity because of the atmosphere,” Faustine says. “The other thing that is super important is that you can change the instruments [...] you can upgrade and repair them with state-of-the-art technology.”

This effectively means that one single telescope can be used for many, many years, which over time can be both more cost and resource efficient. As an example, parts of the spectrograph — an instrument that splits up light into its component colours — of the VLT’s decommissioned SINFONI instrument have been upgraded and are now used in one of its newest instruments, ERIS.

The most obvious contribution, however, is to look into our own impact on climate change and do all we can to minimise our emissions of greenhouse gases. ESO has audited its own climate impact to identify the areas in which we can decrease it, and has put forth measures to do so. These include addressing our energy use, travel and equipment design. For example, the observatories in Chile require large quantities of power to operate, and by implementing more sustainable and cheaper ways to produce that power, we can reduce our impact. What better way, say, to explore the Universe than using the energy produced by our own star? La Silla, Paranal and the ELT construction site are all supported by solar power plants; any excess power is fed into the Chilean power grid. Nonetheless, astronomers place demands on the environment through their professional activities and ESO recognises its responsibility to build towards a sustainable future. It is a challenge that requires the cooperation of all, for the sake of our whole planet.

Keeping the future bright

Julia, while acknowledging that climate monitoring work needs to continue, is optimistic, “we are on a good track that observing in the near-infrared is still a good idea even in 20 and 30 years time (...) Northern Chile remains one of [the best] if not the very best site to do optical and near-infrared observations in the world.”

The results gathered from ESO sites could have broader implications. “I found that quite interesting, as [we are at] an intersection between where astronomy can be helped by climate science, but also where we can help climate science,” Julia says. Most studies thus far on turbulence, for example, have been conducted in the Northern hemisphere. There are also few monitoring stations at especially high altitudes, such as at Chajnantor. “[Climate scientists] can use this data now to maybe incorporate that into their studies.”

Angel emphasises this importance of collaborative and interdisciplinary work. “One thing I love about science is that we are a community [...] We are all looking at problems from different angles.”

At ESO’s observing sites in Chile, there is already extensive planning for the future. Just 20 kilometres east of Paranal, the 39-metre ELT is being built. For the ELT, there is a weather group working proactively with questions related to the changing climate at the site, a group which Julien is an integral part of.

The ELT, among other science aims, will transform our understanding of exoplanets, the field in which Faustine and Julien’s research is focused. “We do this to learn how life appeared and how the planets formed,” Julien says, “which is something really exciting for us to understand, but we also need to understand that these worlds are thousands of light years away, we'll never go there, and that there is no planet B”. Faustine and Julien both agree that astronomers have an important part to play in the fight against climate change. “We have a voice, and we can raise it because, as astronomers, our voices are listened to, which I think is pretty amazing,” Faustine concludes.

Notes

[1] In Julia and Angel’s work, they had data for La Silla between 2010 and 2023, for Paranal from 1998 to 2023 and 1984 to 1998, and for Chajnantor from 1999 to 2005 and 2006 to 2023.

Links

Biography Rebecca Forsberg

Rebecca was a science communication intern at ESO. Prior to this position she completed a bachelors and masters degree in astronomy & astrophysics, and recently completed a PhD at Lund Observatory, Sweden. Rebecca found her passion for writing and communicating science as a science reporter for the Swedish magazines Populär Astronomi and Lundagård.

Biography Pamela Freeman

Pamela Freeman is a PhD candidate in astronomy at the University of Calgary, Canada, studying the chemical makeup and evolution of star forming regions in the Milky Way using submillimetre telescopes. Previously, in her Master’s, she delved into astronomical instrumentation, developing a correlator for the Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory. Throughout these degrees, Pamela has written for the university’s student newspaper, co-developed an outreach video series and has led several student-oriented events. She is bringing her astronomical knowledge and eagerness to learn about all aspects of science, including communication, to ESO.