Press Release

The Vanishing Star

8 December 1988

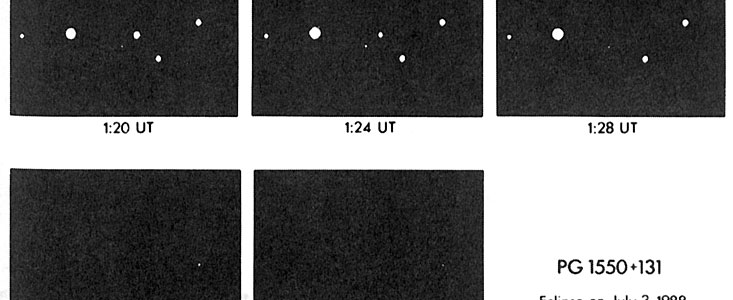

Reinhold Häfner, visiting astronomer at the ESO La Silla Observatory, got his life's surprise when the star on the screen in front of him suddenly was gone. All the other stars were still visible, but this particular one had simply vanished.

The mysterious, 17 magnitude star (in the constellation Ophiuchus) has the designation PG 1550+131 and was first observed at the Palomar Observatory in the mid-seventies. At that time, it was found to have an unusual blue colour. Later observations indicated that its brightness varies somewhat, and Dr. Häfner had therefore decided to have a closer look at it. He thought that it might belong to a relatively rare type of stars, known as "cataclysmic variables".

"Cataclysmic variables" are double (binary) stars in which one of the two components has already gone through its entire evolution and has now become a small, compact object. The other star in the system is still in the main phase of its life, burning hydrogen into helium. The two stars orbit around each other, and there is a steady stream of gas from the larger star to the smaller one. This phenomenon sometimes gives rise to an abrupt increase in brightness; hence the term cataclysmic variable".

Less than two dozen binary stars are known which are presently in the state that immediately precedes the "cataclysmic" phase. They are known as "pre-cataclysmic binaries". In this phase, there is not yet a gas stream from the larger component. However, due to scarcity of accurate data, relatively little is known about binary stars in this transitory phase, for instance about the sizes of the stars, their temperatures, masses, orbital periods, etc. But the exact nature of "pre-cataclysmic binaries" must be known in order to fully understand the violent processes during the unstable "cataclysmic" phase.

Thanks to the occurence of pronounced eclipses of PG 1550+131, it may now become possible to learn more about this important "missing link" in the evolution of binary stars. The analysis of exactly how the light changes during an eclipse, allows to determine the physical properties of the system, e.g. the size of the components, the size and shape of the orbit, the distribution of light on the surfaces of the components, their temperatures, etc. These numbers then place constraints on the corresponding values for "cataclysmic variables".

The eclipses in PG 1550+131 obviously happen when the smaller and brighter of the two stars in the system (the one which is more evolved) during its orbital motion passes behind the other star, as seen from the Earth.

The "depth" of the eclipse, i.e. the amount of light lost, is a record 99%, or even more [1]. This means that the secondary component - whose light is the only light left during the eclipse - is more than 100 times fainter than the star which it eclipses. Moreover, the very short duration of the eclipse - another record - indicates that the faint star is also very small; it is termed a "red dwarf" and its temperature is "only" about 3000 degrees.

Contrarily, the brighter of the two stars is of the "white dwarf" type with a surface temperature of 18 000 degrees. Interestingly, that hemisphere of the fainter "red dwarf" which faces the "white dwarf" is heated to about 6000 degrees. The orbital period in the system is only 187 minutes and the distance between the two components is about 700,000 kilometres. That means that the entire binary system could be contained within the space filled by our Sun.

Immediately after the discovery of the eclipses, spectra were obtained of PG 1550+131 with the ESO 3.6 m telescope, and they support this interpretation.

Notes

[1] In astronomical terms, the eclipse has a central depth of at least 5 magnitudes; the duration is less than 12 minutes

The designation means ``Herbig-Haro type object no. 111''. The astronomers George Herbig (USA) and Guillermo Haro (Mexico) discovered the first objects of this class in the early 1950's, although the underlying astrophysical phenomena have only recently become more fully understood. On celestial photographs they are seen as small, bright nebulae, always in front of large interstellar clouds. The Herbig-Haro nebulae emit light mainly from excited hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and sulphur atoms.

More information

More observations are planned for mid-1989, which will hopefully lead to a refinement of the photometric and spectroscopic data. In the meantime, Dr. Häfner has submitted the preliminary findings for publication in the European journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Contacts

Richard West

ESO

Garching, Germany

Tel: +49 89 3200 6276

Email: information@eso.org

About the Release

| Release No.: | eso8809 |

| Legacy ID: | PR 09/88 |

| Name: | PG 1550+131 |

| Type: | Milky Way : Star : Grouping : Binary |

| Facility: | Danish 1.54-metre telescope |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.