Press Release

Beautiful nebula, violent history: clash of stars solves stellar mystery

11 April 2024

When astronomers looked at a stellar pair at the heart of a stunning cloud of gas and dust, they were in for a surprise. Star pairs are typically very similar, like twins, but in HD 148937, one star appears younger and, unlike the other, is magnetic. New data from the European Southern Observatory (ESO) suggest there were originally three stars in the system, until two of them clashed and merged. This violent event created the surrounding cloud and forever altered the system’s fate.

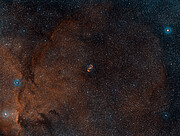

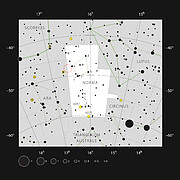

“When doing background reading, I was struck by how special this system seemed,” says Abigail Frost, an astronomer at ESO in Chile and lead author of the study published today in Science. The system, HD 148937, is located about 3800 light-years away from Earth in the direction of the Norma constellation. It is made up of two stars much more massive than the Sun and surrounded by a beautiful nebula, a cloud of gas and dust. “A nebula surrounding two massive stars is a rarity, and it really made us feel like something cool had to have happened in this system. When looking at the data, the coolness only increased.”

“After a detailed analysis, we could determine that the more massive star appears much younger than its companion, which doesn't make any sense since they should have formed at the same time!” Frost says. The age difference — one star appears to be at least 1.5 million years younger than the other — suggests something must have rejuvenated the more massive star.

Another piece of the puzzle is the nebula surrounding the stars, known as NGC 6164/6165. It is 7500 years old, hundreds of times younger than both stars. The nebula also shows very high amounts of nitrogen, carbon and oxygen. This is surprising as these elements are normally expected deep inside a star, not outside; it is as if some violent event had set them free.

To unravel the mystery, the team assembled nine years' worth of data from the PIONIER and GRAVITY instruments, both on ESO’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), located in Chile’s Atacama Desert. They also used archival data from the FEROS instrument at ESO’s La Silla Observatory.

“We think this system had at least three stars originally; two of them had to be close together at one point in the orbit whilst another star was much more distant,” explains Hugues Sana, a professor at KU Leuven in Belgium and the principal investigator of the observations. “The two inner stars merged in a violent manner, creating a magnetic star and throwing out some material, which created the nebula. The more distant star formed a new orbit with the newly merged, now-magnetic star, creating the binary we see today at the centre of the nebula.”

“The merger scenario was already in my head back in 2017 when I studied nebula observations obtained with the European Space Agency’s Herschel Space Telescope,” adds co-author Laurent Mahy, currently a senior researcher at the Royal Observatory of Belgium. “Finding an age discrepancy between the stars suggests that this scenario is the most plausible one and it was only possible to show it with the new ESO data.”

This scenario also explains why one of the stars in the system is magnetic and the other is not — another peculiar feature of HD 148937 spotted in the VLTI data.

At the same time, it helps solve a long-standing mystery in astronomy: how massive stars get their magnetic fields. While magnetic fields are a common feature of low-mass stars like our Sun, more massive stars cannot sustain magnetic fields in the same way. Yet some massive stars are indeed magnetic.

Astronomers had suspected for some time that massive stars could acquire magnetic fields when two stars merge. But this is the first time researchers find such direct evidence of this happening. In the case of HD 148937, the merger must have happened recently. “Magnetism in massive stars isn't expected to last very long compared to the lifetime of the star, so it seems we have observed this rare event very soon after it happened,” Frost adds.

ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), currently under construction in the Chilean Atacama Desert, will enable researchers to work out what happened in the system in more detail, and perhaps reveal even more surprises.

More information

This research was presented in a paper entitled “A magnetic massive star has experienced a stellar merger” published in Science (www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adg7700).

It has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement number 772225: MULTIPLES; PI: Hugues Sana).

The team is composed of A. J. Frost (European Southern Observatory, Santiago, Chile [ESO Chile] and Institute of Astronomy, KU Leuven, Belgium [KU Leuven]), H. Sana (KU Leuven), L. Mahy (Royal Observatory of Belgium, Belgium and KU Leuven), G. Wade (Department of Physics & Space Science, Royal Military College of Canada, Canada [RMC Space Science]), J. Barron (Department of Physics, Engineering & Astronomy, Queen’s University, Canada and RMC Space Science), J.-B. Le Bouquin (Université Grenoble Alpes, Centre national de la Recherche Scientifique, Institute de Planétologie et d’Astrophyisique de Grenoble, France), A. Mérand (European Southern Observatory, Garching, Germany [ESO]), F. R. N. Schneider (Heidelberger Institut für Theoretische Studien, Germany and Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Germany), T. Shenar (The School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel Aviv University, Israel and KU Leuven), R. H. Barbá (Departamento de Física y Astronomía, Universidad de La Serena, Chile), D. M. Bowman (School of Mathematics, Statistics and Physics, Newcastle University, UK and KU Leuven), M. Fabry (KU Leuven), A. Farhang (School of Astronomy, Institute for Research in Fundamental Sciences, Iran), P. Marchant (KU Leuven), N. I. Morrell (Las campanas Observatory, Carnegie Observatories, Chile) and J. V. Smoker (ESO Chile and UK Astronomy Technology centre, Royal Observatory, UK).

The European Southern Observatory (ESO) enables scientists worldwide to discover the secrets of the Universe for the benefit of all. We design, build and operate world-class observatories on the ground — which astronomers use to tackle exciting questions and spread the fascination of astronomy — and promote international collaboration for astronomy. Established as an intergovernmental organisation in 1962, today ESO is supported by 16 Member States (Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), along with the host state of Chile and with Australia as a Strategic Partner. ESO’s headquarters and its visitor centre and planetarium, the ESO Supernova, are located close to Munich in Germany, while the Chilean Atacama Desert, a marvellous place with unique conditions to observe the sky, hosts our telescopes. ESO operates three observing sites: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. At Paranal, ESO operates the Very Large Telescope and its Very Large Telescope Interferometer, as well as survey telescopes such as VISTA. Also at Paranal ESO will host and operate the Cherenkov Telescope Array South, the world’s largest and most sensitive gamma-ray observatory. Together with international partners, ESO operates ALMA on Chajnantor, a facility that observes the skies in the millimetre and submillimetre range. At Cerro Armazones, near Paranal, we are building “the world’s biggest eye on the sky” — ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope. From our offices in Santiago, Chile we support our operations in the country and engage with Chilean partners and society.

Links

- Research paper (preprint)

- Photos of the VLT/VLTI

- Find out more about ESO's Extremely Large Telescope on our dedicated website and press kit

- For journalists: subscribe to receive our releases under embargo in your language

- For scientists: got a story? Pitch your research

Contacts

Abigail Frost

European Southern Observatory

Santiago, Chile

Tel: +44 79 8353 9292

Email: Abigail.Frost@eso.org

Hugues Sana

KU Leuven

Leuven, Belgium

Tel: +32 479 50 46 73

Email: hugues.sana@kuleuven.be

Laurent Mahy

Royal Observatory of Belgium

Brussels, Belgium

Tel: +32 476 23 60 06

Email: laurent.mahy@oma.be

Bárbara Ferreira

ESO Media Manager

Garching bei München, Germany

Tel: +49 89 3200 6670

Cell: +49 151 241 664 00

Email: press@eso.org

Lê Binh San PHAM

Communication Officer, Royal Observatory of Belgium

Brussels, Belgium

Email: lebinhsan.pham@oma.be

About the Release

| Release No.: | eso2407 |

| Name: | HD 148937, NGC 6164, NGC 6165 |

| Type: | Milky Way : Star : Grouping : Binary Milky Way : Nebula |

| Facility: | Very Large Telescope Interferometer |

| Instruments: | FEROS, GRAVITY, PIONIER |

| Science data: | 2024Sci...384..214F |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.