Press Release

Stars Born in Winds from Supermassive Black Holes

ESO’s VLT spots brand-new type of star formation

27 March 2017

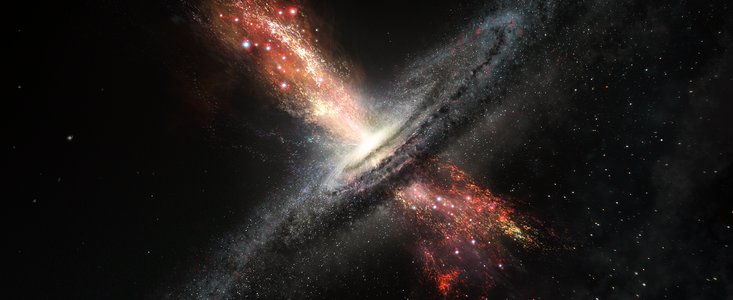

Observations using ESO’s Very Large Telescope have revealed stars forming within powerful outflows of material blasted out from supermassive black holes at the cores of galaxies. These are the first confirmed observations of stars forming in this kind of extreme environment. The discovery has many consequences for understanding galaxy properties and evolution. The results are published in the journal Nature.

A UK-led group of European astronomers used the MUSE and X-shooter instruments on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile to study an ongoing collision between two galaxies, known collectively as IRAS F23128-5919, that lie around 600 million light-years from Earth. The group observed the colossal winds of material — or outflows — that originate near the supermassive black hole at the heart of the pair’s southern galaxy, and have found the first clear evidence that stars are being born within them [1].

Such galactic outflows are driven by the huge energy output from the active and turbulent centres of galaxies. Supermassive black holes lurk in the cores of most galaxies, and when they gobble up matter they also heat the surrounding gas and expel it from the host galaxy in powerful, dense winds [2].

“Astronomers have thought for a while that conditions within these outflows could be right for star formation, but no one has seen it actually happening as it’s a very difficult observation,” comments team leader Roberto Maiolino from the University of Cambridge. “Our results are exciting because they show unambiguously that stars are being created inside these outflows.”

The group set out to study stars in the outflow directly, as well as the gas that surrounds them. By using two of the world-leading VLT spectroscopic instruments, MUSE and X-shooter, they could carry out a very detailed study of the properties of the emitted light to determine its source.

Radiation from young stars is known to cause nearby gas clouds to glow in a particular way. The extreme sensitivity of X-shooter allowed the team to rule out other possible causes of this illumination, including gas shocks or the active nucleus of the galaxy.

The group then made an unmistakable direct detection of an infant stellar population in the outflow [3]. These stars are thought to be less than a few tens of millions of years old, and preliminary analysis suggests that they are hotter and brighter than stars formed in less extreme environments such as the galactic disc.

As further evidence, the astronomers also determined the motion and velocity of these stars. The light from most of the region’s stars indicates that they are travelling at very large velocities away from the galaxy centre — as would make sense for objects caught in a stream of fast-moving material.

Co-author Helen Russell (Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK) expands: “The stars that form in the wind close to the galaxy centre might slow down and even start heading back inwards, but the stars that form further out in the flow experience less deceleration and can even fly off out of the galaxy altogether.”

The discovery provides new and exciting information that could better our understanding of some astrophysics, including how certain galaxies obtain their shapes [4]; how intergalactic space becomes enriched with heavy elements [5]; and even from where unexplained cosmic infrared background radiation may arise [6].

Maiolino is excited for the future: “If star formation is really occurring in most galactic outflows, as some theories predict, then this would provide a completely new scenario for our understanding of galaxy evolution.”

Notes

[1] Stars are forming in the outflows at a very rapid rate; the astronomers say that stars totalling around 30 times the mass of the Sun are being created every year. This accounts for over a quarter of the total star formation in the entire merging galaxy system.

[2] The expulsion of gas through galactic outflows leads to a gas-poor environment within the galaxy, which could be why some galaxies cease forming new stars as they age. Although these outflows are most likely to be driven by massive central black holes, it is also possible that the winds are powered by supernovae in a starburst nucleus undergoing vigorous star formation.

[3] This was achieved through the detection of signatures characteristic of young stellar populations and with a velocity pattern consistent with that expected from stars formed at high velocity in the outflow.

[4] Spiral galaxies have an obvious disc structure, with a distended bulge of stars in the centre and surrounded by a diffuse cloud of stars called a halo. Elliptical galaxies are composed mostly of these spheroidal components. Outflow stars that are ejected from the main disc could give rise to these galactic features.

[5] How the space between galaxies — the intergalactic medium — becomes enriched with heavy elements is still an open issue, but outflow stars could provide an answer. If they are jettisoned out of the galaxy and then explode as supernovae, the heavy elements they contain could be released into this medium.

[6] Cosmic-infrared background radiation, similar to the more famous cosmic microwave background, is a faint glow in the infrared part of the spectrum that appears to come from all directions in space. Its origin in the near-infrared bands, however, has never been satisfactorily ascertained. A population of outflow stars shot out into intergalactic space may contribute to this light.

More information

This research was presented in a paper entitled “Star formation in a galactic outflow” by Maiolino et al., to appear in the journal Nature on 27 March 2017.

The team is composed of R. Maiolino (Cavendish Laboratory; Kavli Institute for Cosmology, University of Cambridge, UK), H.R. Russell (Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK), A.C. Fabian (Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK), S. Carniani (Cavendish Laboratory; Kavli Institute for Cosmology, University of Cambridge, UK), R. Gallagher (Cavendish Laboratory; Kavli Institute for Cosmology, University of Cambridge, UK), S. Cazzoli (Departamento de Astrofisica-Centro de Astrobiología, Madrid, Spain), S. Arribas (Departamento de Astrofisica-Centro de Astrobiología, Madrid, Spain), F. Belfiore ((Cavendish Laboratory; Kavli Institute for Cosmology, University of Cambridge, UK), E. Bellocchi (Departamento de Astrofisica-Centro de Astrobiología, Madrid, Spain), L. Colina (Departamento de Astrofisica-Centro de Astrobiología, Madrid, Spain), G. Cresci (Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Firenze, Italy), W. Ishibashi (Universität Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland), A. Marconi (Università di Firenze, Italy; Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Firenze, Italy), F. Mannucci (Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Firenze, Italy), E. Oliva (Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Firenze, Italy), and E. Sturm (Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Garching, Germany).

ESO is the foremost intergovernmental astronomy organisation in Europe and the world’s most productive ground-based astronomical observatory by far. It is supported by 16 countries: Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Czechia, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, along with the host state of Chile. ESO carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities enabling astronomers to make important scientific discoveries. ESO also plays a leading role in promoting and organising cooperation in astronomical research. ESO operates three unique world-class observing sites in Chile: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. At Paranal, ESO operates the Very Large Telescope, the world’s most advanced visible-light astronomical observatory and two survey telescopes. VISTA works in the infrared and is the world’s largest survey telescope and the VLT Survey Telescope is the largest telescope designed to exclusively survey the skies in visible light. ESO is a major partner in ALMA, the largest astronomical project in existence. And on Cerro Armazones, close to Paranal, ESO is building the 39-metre European Extremely Large Telescope, the E-ELT, which will become “the world’s biggest eye on the sky”.

Links

Contacts

Roberto Maiolino

Cavendish Laboratory, Kavli Institute for Cosmology

University of Cambridge, UK

Email: r.maiolino@mrao.cam.ac.uk

Richard Hook

ESO Public Information Officer

Garching bei München, Germany

Tel: +49 89 3200 6655

Cell: +49 151 1537 3591

Email: rhook@eso.org

About the Release

| Release No.: | eso1710 |

| Name: | IRAS F23128-5919 |

| Type: | Early Universe : Galaxy : Activity : AGN Early Universe : Galaxy : Component : Central Black Hole |

| Facility: | Very Large Telescope |

| Instruments: | MUSE, X-shooter |

| Science data: | 2017Natur.544..202M |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.