Press Release

It Is No Mirage!

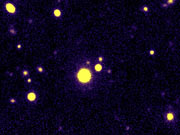

Large Telescopes Team Up to Help Astronomers Discover a Trio of Quasars

8 January 2007

Using ESO's Very Large Telescope and the W.M. Keck Observatory, astronomers at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland and the California Institute of Technology, USA, have discovered what appears to be the first known triplet of quasars. This close trio of supermassive black holes lies about 10.5 billion light-years away towards the Virgo (The Virgin) constellation.

"Quasars are extremely rare objects," says George Djorgovski, from Caltech and leader of the team that made the discovery. "To find two of them so close together is very unlikely if they were randomly distributed in space. To find three is unprecedented."

The findings are being reported at the winter 2007 meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle, USA.

Quasars are extraordinary luminous objects in the distant universe, thought to be powered by supermassive black holes at the heart of galaxies. A single quasar could be a thousand times brighter than an entire galaxy of a hundred billion stars, and yet this remarkable amount of energy originates from a volume smaller than our solar system. About a hundred thousand quasars have been found to date, and among them several tens of close pairs, but this is the first known case of a close triple quasar system.

Quasars (QUAsi StellAR Sources) were first discovered in 1963 by the Dutch-American astronomer Maarten Schmidt at the Palomar Observatory (California, USA) and the name refers to their 'star-like' appearance on the images obtained at that time. Distinguishing them from stars is thus no easy task and discovering a close trio of such objects is even less obvious.

The feat could only be accomplished by combining images from two of the largest ground-based telescopes, ESO's 8.2-m Very Large Telescope at Cerro Paranal, in Chile, and the W. M. Keck Observatory's 10-m telescope atop Mauna Kea, Hawaii, as well as using a very sophisticated and efficient image sharpening method.

The distant quasar LBQS 1429-008 was first discovered in 1989 by an international team of astronomers led by Paul Hewett of the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge, England. Hewett and his collaborators found a fainter companion to their quasar, and proposed that it was a case of gravitational lensing. According to Einstein's general theory of relativity, if a large mass (such as a big galaxy or a cluster of galaxies) is placed along the line of sight to a distant quasar, the light rays are bent, and an observer on Earth will see two or more close images of the quasar â a cosmic mirage. The first such gravitational lens was discovered in 1979, and hundreds of cases are now known. However, several groups over the past several years cast doubts that this system is a gravitational lens, and proposed instead that it is a close physical pair of quasars.

What the Caltech-Swiss team has found is that there is a third, even fainter quasar associated with the previously known two. The three quasars have the same redshift, hence, are at the same distance from us.

The astronomers performed an extensive theoretical modeling, trying to explain the observed geometry of the three images as a consequence of gravitational lensing. "We just could not reproduce the data," says Frédéric Courbin of Lausanne. "It is essentially impossible to account for what we see using reasonable gravitational lensing models."

Moreover, there is no trace of a possible lensing galaxy, which would be needed if the system were a gravitational lens. The team has also documented small, but significant differences in the properties of the three quasars. These are much easier to understand if the three quasars are physically distinct objects, rather than gravitational lensing mirages. Combining all these pieces of evidence effectively eliminated lensing as a possible explanation.

"We were left with an even more exciting possibility that this is an actual triple quasar," says Georges Meylan, also from Lausanne. The three quasars are separated by only about 100,000 to 150,000 light-years, which is about the size of our own Milky Way.

Gravitational lensing can be used to probe the distribution of dark and visible mass in the universe, but quasar pairs -and now a triplet- provide astronomers with a different kind of insight.

"Quasars are believed to be powered by gas falling into supermassive black holes," says Djorgovski. "This process happens very effectively when galaxies collide or merge, and we are observing this system at the time in the cosmic history when such galaxy interactions were at a peak."

If galaxy interactions were responsible for the quasar activity, having two quasars close together would be much more likely than if they were randomly distributed in space. This may explain the unusual abundance of binary quasars, which have been reported by several groups. "In this case, we are lucky to catch a rare situation where quasars are ignited in three interacting galaxies," says Ashish Mahabal, one of the Caltech scientists involved in the study.

Discoveries of more such systems in the future may help astronomers understand better the fundamental relationship between the formation and evolution of galaxies, and the supermassive black holes in their cores, now believed to be common in most large galaxies, our own Milky Way included.

This work is also described in a paper submitted to the Astrophysical Journal Letters. The team is composed of S. George Djorgovski, Ashish Mahabal, and Eilat Glikman of Caltech (USA), Frédéric Courbin, Georges Meylan and Dominique Sluse of the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (Switzerland), and David Thompson of the University of Arizona's Large Binocular Telescope Observatory (USA).

Contacts

Georges Meylan

Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne

Lausanne, France

Tel: +41 22 379 24 25

Cell: (Sauverny): +41 22 379 24 25

Email: Georges.Meylan@epfl.ch

S. George Djorgovski

Caltech Astronomy

USA

Tel: +1 (626) 395-4415

Email: george@astro.caltech.edu

About the Release

| Release No.: | eso0702 |

| Legacy ID: | PR 02/07 |

| Name: | QQQ 1429-008 |

| Type: | Early Universe : Galaxy : Activity : AGN : Quasar |

| Facility: | Very Large Telescope, W. M. Keck Observatory |

| Instruments: | FORS1 |

| Science data: | 2007ApJ...662L...1D |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.