- How and why astronomical images are processed

- What kind of objects and phenomena ESO’s visual artists recreate

- Where artists get their inspiration for illustrating things that we can’t see

Q. First of all, why don’t we show the images as they are collected by the telescopes and how do you transform raw telescope images into stunning images of the cosmos?

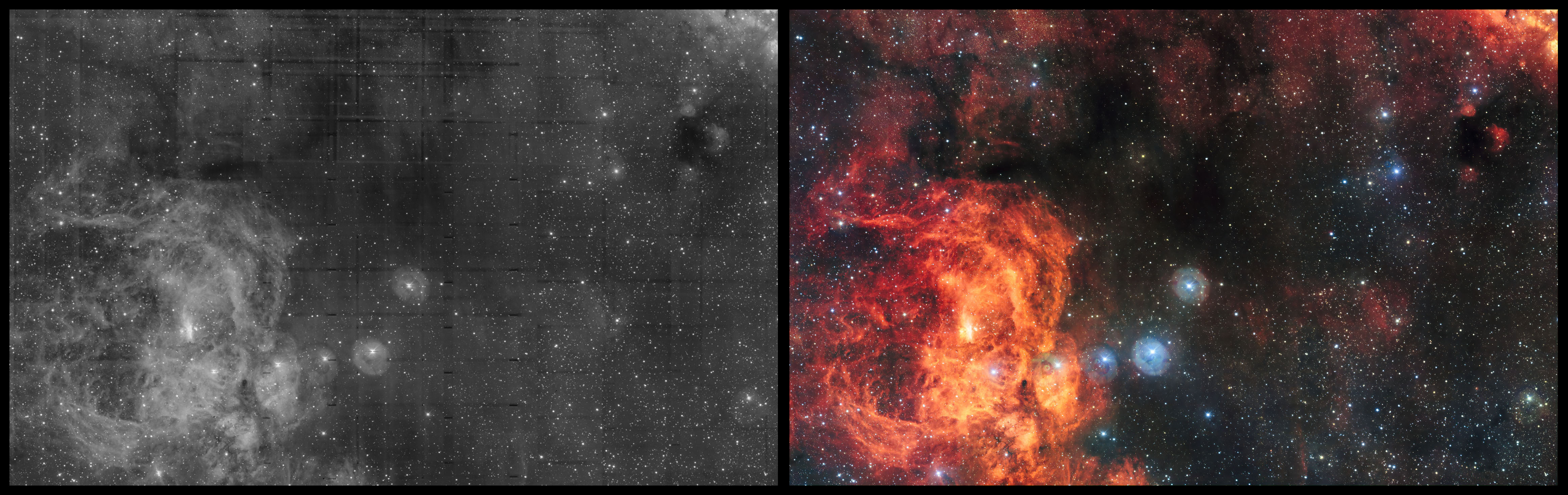

MK: We initially get many images of the same object, each of which is a record of a different wavelength of light. These images come in FITS format — a digital file format that is commonly used in astronomy. We assign a colour to each wavelength and layer these images on top of each other to make one nice coloured image.

Below is an image before and after I processed it. Some images are more difficult to process than others; a mosaic image from ESO’s VLT Survey Telescope (VST), for example, involves a lot more work than a Hubble Space Telescope image, because it contains billions of pixels. The challenge with giant images is that they need to look good when you zoom out and also when you zoom in. But in the end, the VST wide-angle images are among my favourites. Totally worth all the effort.

Q. How do you create an artist’s impression to visualise something we can’t yet image directly, like the surface of an exoplanet?

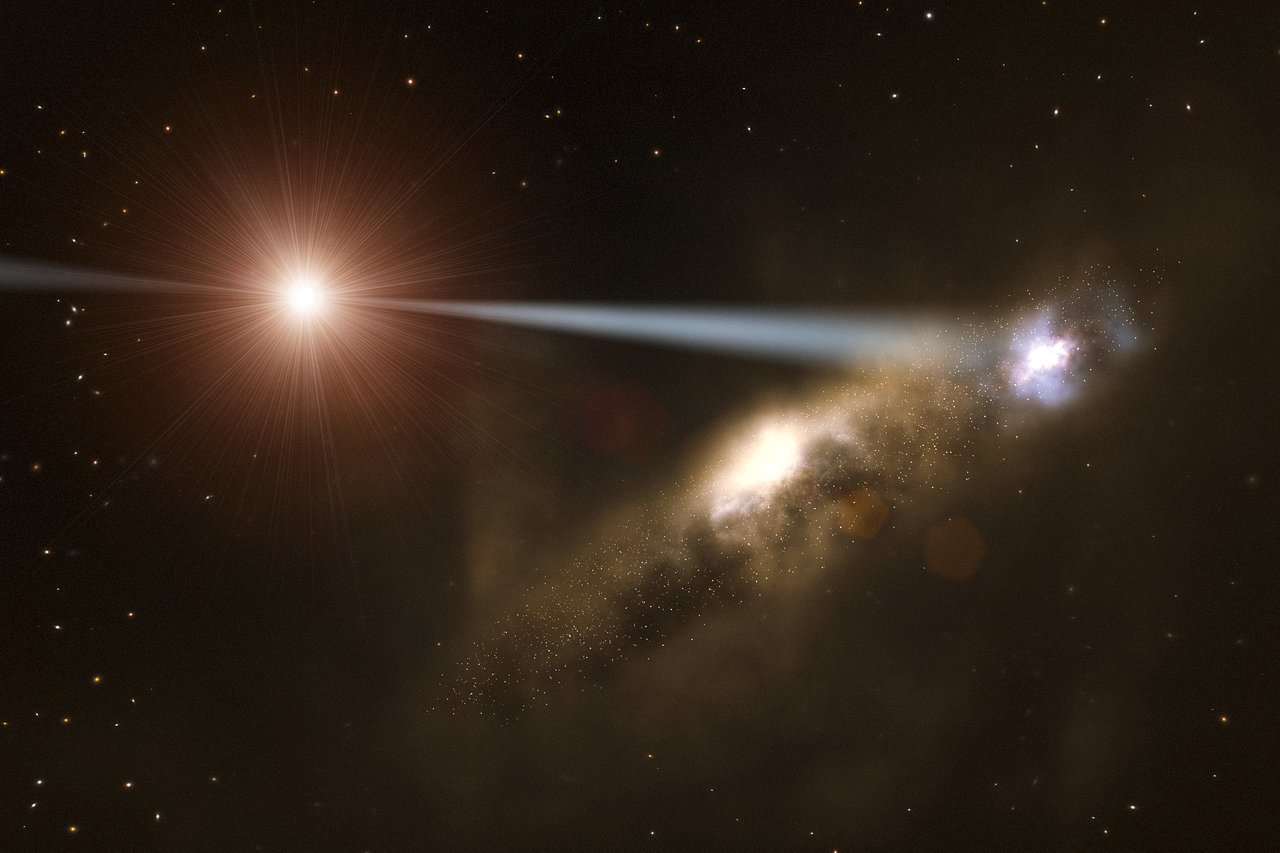

Luis Calçada (LC): Often, we cannot see them close up, but scientific analysis reveals most of the physical processes behind these objects or events. This means that we can usually (at least partly!) guess how something looks. We know the velocities, we know the scales, we know the temperature, and that all translates into something physical, something visual. For example, if an object has a certain temperature then we know it emits radiation at a certain wavelength, so we can assign colours to it.

That’s exactly why it’s interesting to create these images, because we can work out how an object looks to some extent. It’s not just down to the imagination, it is also based on science.

Q. How long does it take you to create an image or an animation?

LC: We’ve had cases where we have spent a couple of weeks on some stuff when it is very important, like for the images and simulations we created for the release of the first image of a black hole earlier this year. But for weekly press releases sometimes we take just one or two days. Some things are quicker than others; we’ve done so many exoplanets, for example, that for them it’s just a case of changing the colour and composition to match the new observations. It’s different when we’re drawing or animating something completely new.

Q. What does a typical working day at ESO look like for you?

MK: Luckily there are no typical days at work for me. I'm fortunate to be able to work with talented people on a lot of different projects. We work on visuals for the ESO site, for the ESO Supernova Planetarium & Visitor Centre, and also the Hubble Space Telescope, so it doesn't get boring very often.

The best days for me are of course the ones where I am let off the leash, allowed to do whatever I want without restrictions, such as illustrating abstract physical phenomena in frontier science where nobody really knows what it should look like. A dream for every artist.

Q. How did you come into this role? Is this a career you always knew you wanted?

LC: When I was studying astronomy, I started working in a planetarium and I thought, “oh, we need some visuals for this”, so I gave it a go. I started teaching myself about computer graphics and astronomy animation, and continued developing my skills in that direction before ending up at ESO. Illustration was not something I’d thought about as a kid but when I got into it, I really enjoyed it. So for me, combining illustration with astronomy at ESO is the best place I could be.

Martin is a graphics designer which is nice because we really complement each other. He has the formal art background and I have the astronomical one. He has already been working here for something like twenty years though, so by now he’s got a pretty good knowledge of astrophysics!

Q. Martin, when you started working at ESO, image processing technology must have been quite different. How has the software changed over the years and how does that impact your work?

MK: Besides the very much improved computer power and reliability, actually not much has changed. Although artificial intelligence is coming into play more and more, for example for sharpening, noise reduction etc., the most important things are still to have a clear vision of where you want to go, and being careful not to overdo it. My motto is "Maximum Natural", meaning I try to squeeze everything out of the data without going overboard.

Q. Do you have an idea of the impact your images or animations have online or in the media?

LC: Since I joined ESO thirteen years ago, I have produced a lot of images that have been used on book covers and even on Wikipedia. It’s interesting when you look up some phenomena and go onto the Wikipedia page and there’s your image! I feel lucky to have produced some images that go down as the recorded image for a certain phenomena.

MK: For example my illustration of the Solar System ended up as the main image on the Wikipedia page for the Solar System!

Q. What do you think the future will look like for astronomical images?

MK: Over the next few years, two exciting new telescopes will arrive on the scene, the James Webb Space Telescope and the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT). Both will primarily observe near-infrared light, with James Webb providing crisp images from space, and the ELT providing images with an incredible amount of detail.

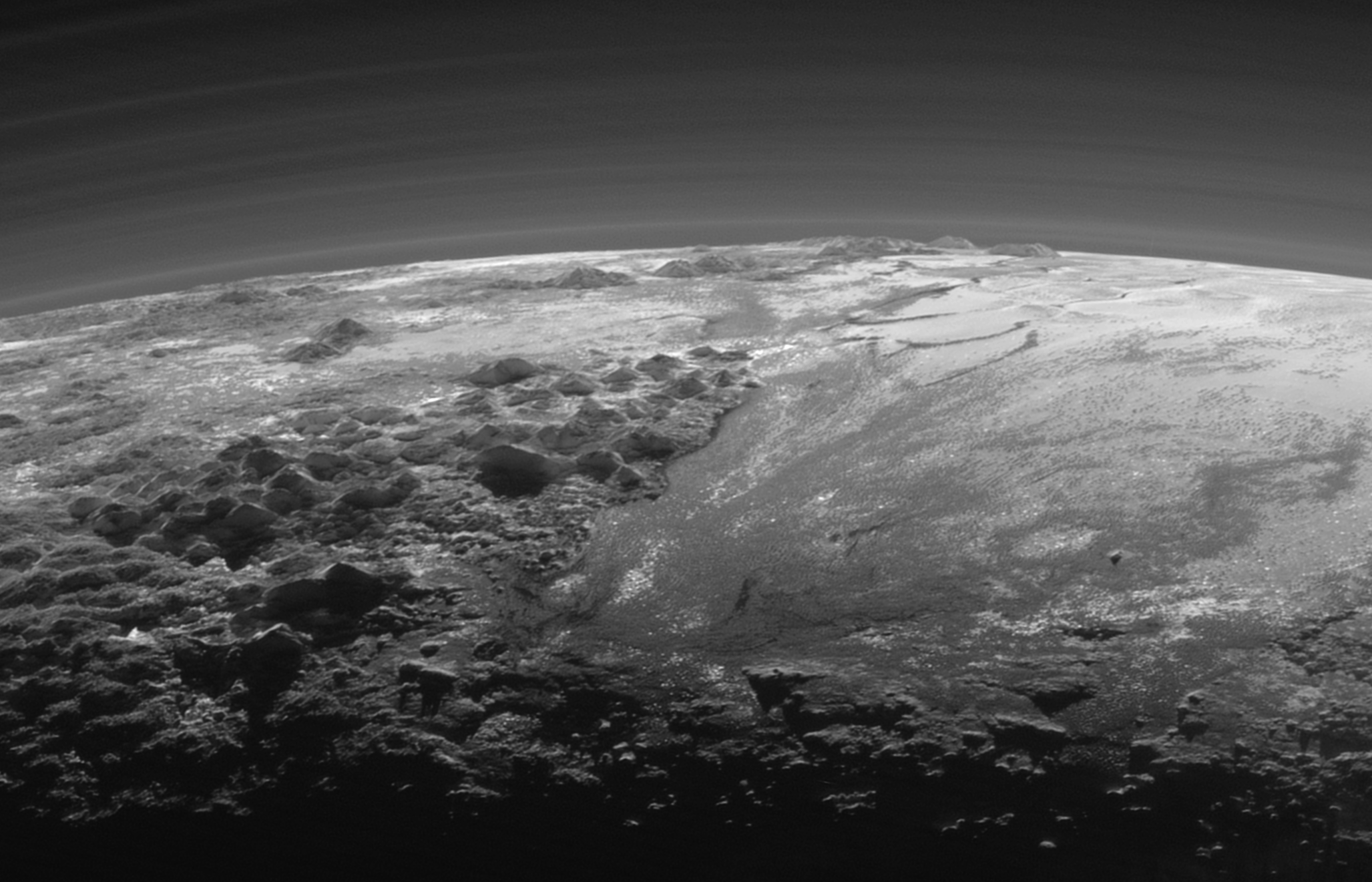

These new telescopes will confront our imagined illustrations with real images, which is always exciting. In 2009 we illustrated the atmosphere of Pluto, way before the New Horizons spacecraft took photos of the planet close-up. The real images were so similar to our illustrations!

Also, I think that in the future images will be processed more and more by artificial intelligence, rather than one person using one computer.

Q. What advice would you give to someone looking to get into space illustration?

MK: My advice for everyone interested in image processing would be; get the best out of the newest technology but don't get carried away. I think we have all seen images which look more like a psychedelic-neon-pizza than a nebula. So don't do everything possible just because it is possible.

Q. What do you think is the most exciting part of your job?

MK: From the feedback we get from the millions of followers and astronomy enthusiasts around the world we know how much people love space images, and how much these images help connect people with the sometimes complicated scientific discoveries that ESO conveys. We seem to touch people on a deep emotional, sometimes even spiritual level with our images; for me, this is probably the most rewarding aspect of our work.

You basically start with a blank sheet of paper and infinite possibilities. It is really fascinating to understand and fully master the tools that we have nowadays. Whether it’s image processing, animations or video editing, aligning the vision of an artist and the hard facts coming from a passionate scientist is pretty cool.

Numbers in this article

| 13 | Number of years that Luis has worked at ESO |

| 20 | Number of years that Martin has worked at ESO |

| 2009 | Year that Luis illustrated the surface of Pluto |

| 1 000 000 000 | Order of magnitude number of pixels in a VLT Survey Telescope mosaic image |

Links

Biography Martin Kornmesser and Luis Calçada

After high school Martin Kornmesser worked as roadie and guitar tech for concert agencies. He then obtained his degree in Graphics Design in Munich in 1989. By the end of 1990 he was the co-founder of design company ART-M. Martin joined ESA's Hubble outreach group at ESO in 1999 and has worked for ESO ever since.

Luis is a Science Visualisation specialist with more than 15 years of experience. He has a degree of Physics and Astronomy from the University of Porto, Portugal. He started his professional career in the planetarium — Centro Multimeios in Espinho Portugal, developing and producing planetarium shows. He has then moved to Munich, Germany to work as a Data Visualization Artist at the European Southern Observatory. Luis spends most of his free time taking photos and making music.