- Why the Southern Cross is featured in the ESO logo

- How this constellation is useful for navigation purposes

- The stories that First Nations people told about this constellation

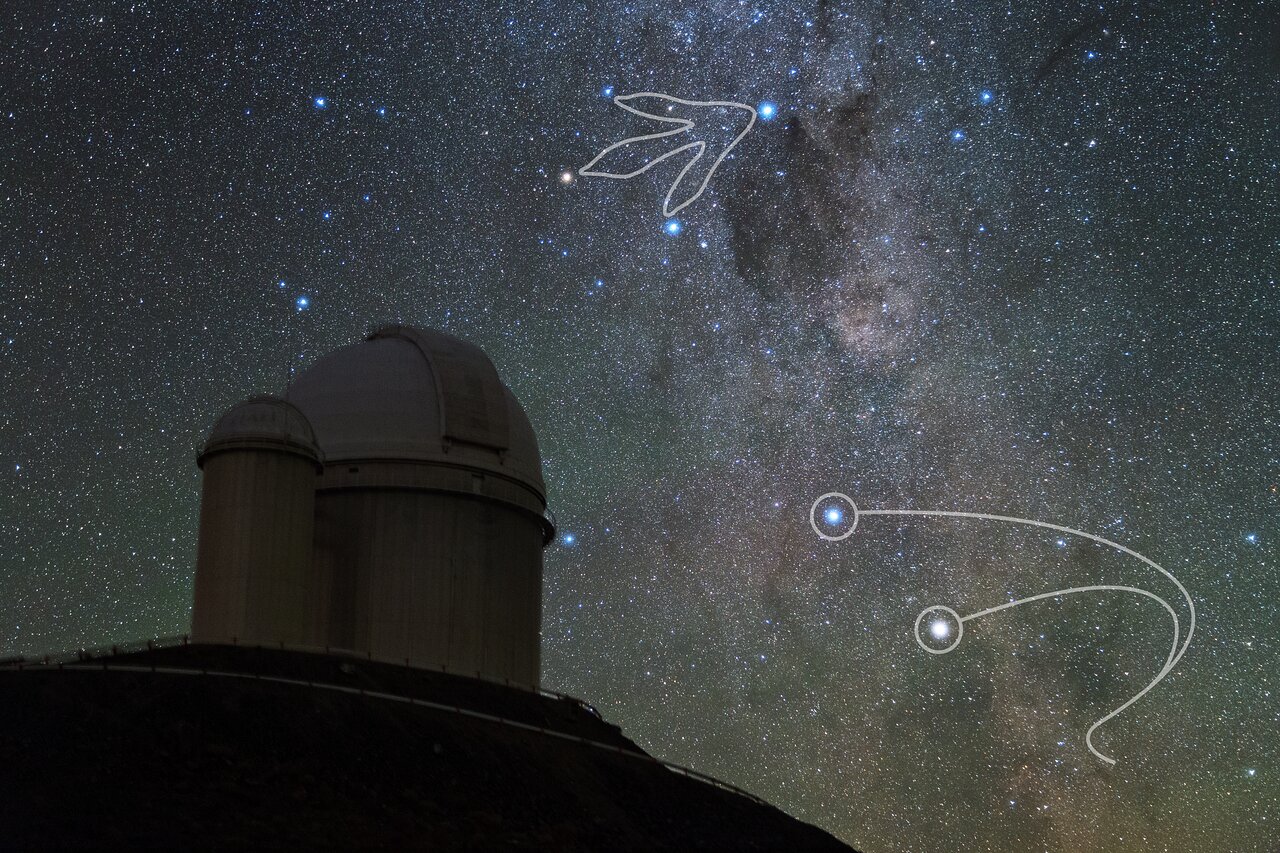

Have you ever noticed the four stars in the logo of the European Southern Observatory (ESO)? They are not arranged randomly: they form the constellation Crux. You might know it better by its common name in English: the Southern Cross. But this pattern of stars has been interpreted in many ways: an ostrich’s footprint, an anchor, a stingray… Let’s travel the world and discover these stories!

For thousands of years, people have been looking up at the sky, in awe and wonder. We give names to constellations and nebulae, and even see the ‘Man in the Moon’. This tendency to perceive figures in a random visual pattern is called pareidolia and helps us make sense of our surroundings.

Pareidolia (per-ī-ˈdō-lē-ə):

the tendency to perceive a specific,

often meaningful image in a random

or ambiguous visual pattern.

In Western Europe, the stories and interpretations of the stars are often linked to Greek mythology, but there are much older interpretations. Babylonian astronomers already observed the stars. And many First Nations people interpreted star patterns, and told stories about them. They analysed their movements, discovered links to their daily lives, such as the passage of seasons, and transferred this knowledge in stories. These first astronomers have looked at what we call the Southern Cross, and gave their own meaning to it.

Tiny constellation, big significance

But first, let’s look at the stars themselves. Crux is the smallest of the 88 constellations officially recognised by the International Astronomical Union. It consists of four main stars, located between 88 and 345 light years from Earth. They are, in order of brightness:

- Alpha Crucis (Acrux), appearing as a single star, but actually a multiple star system

- Beta Crucis (Mimosa), a variable star

- Gamma Crucis (Gacrux), a double star (two unrelated stars that appear close together)

- Delta Crucis (Imai)

Epsilon Crucis is often included in the pattern of the Southern cross, but not always. It didn’t make it onto ESO’s logo, for instance.

Not part of the constellation Crux — but frequently named in the same breath — are Alpha and Beta Centauri, often referred to as the "Southern Pointers" or just "The Pointers". These two bright nearby stars allow people to easily find the Southern Cross in the sky.

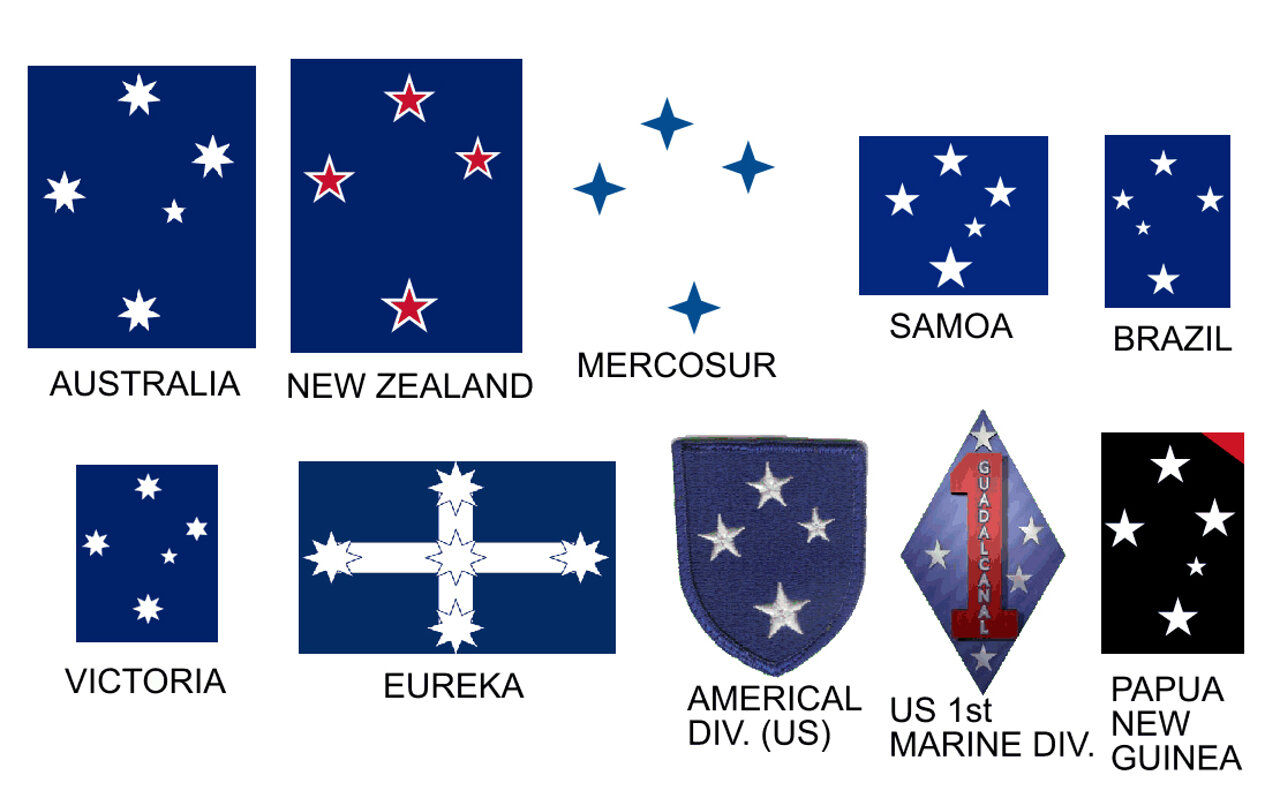

With time, Crux made its way to the flags of Australia, Brazil, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, and Samoa. Sometimes with five stars, sometimes only four. Whatever the number, it is clear that Crux is a true southern icon.

Crux as a navigation beacon

In Chile, where ESO operates its observatories, Crux is clearly visible in the night sky. Like Polaris in the North, Crux Australis — Latin for Southern Cross — is an important beacon in the southern hemisphere. It is circumpolar: it never sets below the horizon as the Earth rotates, and can be seen from anywhere in the southern hemisphere, all year long. On top of that, the foot of the ‘cross’ always points to the south celestial pole, making it ideal for navigation at night in times when no GPS, smartphone or compass were available.

But Crux wasn't only used for navigation. As the Earth orbits the Sun, our view of the night sky changes throughout the year. First Nations people followed the constellations in the sky to track the seasons and to know when to go look for certain foods. By telling stories about the stars, they transferred this knowledge over generations and centuries.

I spy with my little eye… a cross?

The name “Southern Cross” was given by the Europeans, looking at the stars from a European perspective. They took it as a sign of divine blessing for their explorations and throughout time, because of their imperialism, this Christian perspective became the dominant one.

But Crux had much older names too. As early as 1320-1350, settlers from East Polynesia arrived in New Zealand by canoe. Looking at the sky, they saw something totally different.

The anchor of the great sky canoe

For the Māori, the First Nations people of New Zealand, the Crux constellation is known by at least eight different names. Tainui Māori saw the four stars as Te Punga, the anchor of a great sky waka (canoe). To the Māori from the Wairarapa region, the Southern Cross was Māhutonga – an aperture in the Milky Way (Te Ikaroa) through which storm winds blew.

“Nā Māhutonga i tohutohu mai ō koutou tūpuna, me te nui hoki o tō rātou māia, kia whakawhiti ora mai rātou i Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, ki tēnei whenua. / It was the Southern Cross that guided our ancestors and with their bravery they were able to cross the Pacific Ocean safely to this country.” [1]

When the Pacific people voyaged across the open sea to what we today know as New Zealand, they relied on their knowledge of the ocean swells, the winds and, of course, the stars to guide them. Polynesian navigators memorised the location of at least 220 stars, where they come up and where they go down in the night sky.

A hunted ñandú in Chile

Now, let’s cross the South Pacific Ocean and ask the Chileans what they see in the Southern Cross. Today, you might get quite a few different answers. There is the cross, of course. “A kite” will also be a recurring one, as kite flying is a Chilean tradition, especially during National Day celebrations.

For the Mapuche people of south-central Chile, the story around Crux features a ñandú, also called a rhea, a flightless bird similar to an ostrich. Wenuleufü, the river of the sky, is the representation of a hunting field of ñandús. The four stars of Crux are the footprint (for some it’s the leg) of the bird, named Pünonchoike (or Namunchoike) in the Mapudungun language.

In Mapuche cosmology, the story goes that the ñandú left her footprint while escaping from a hunter, chasing her with boleadoras (or bolas), a throwing weapon to capture animals by entangling its legs. The bolas are called Ütrüblükai, and correspond to the "Southern Pointers", Alpha and Beta Centauri.

Today, the footprint is still part of Mapuche tradition: they paint it on horses (sacred horses that are dedicated to Elchenchawe, who lives in the sky), and on youngsters and dancers in some ceremonies. It’s also a common motif in traditional jewellery.

Chasing the ostrich

The ñandú is part of the mythological Universe surrounding the ‘Chase of the ostrich’, which is not restricted to Chile. A cosmic ostrich-like creature pops up in many pre-hispanic cultures in South-America.

In a region known as the Gran Chaco, the core of the story is a group of siblings (often three kids) hunting an ostrich. The ostrich starts flying, the children follow it to the sky, together with a pair of dogs. The dogs catch the ostrich, but don’t kill it. Instead, they remain there and become the Southern Cross.

The Tehuelche people in the eastern Patagonia region have a story similar to that of the Mapuche. Hunters are chasing a male ostrich called Kakn all the way up to the edge of a cliff. Trapped, Kakn runs up a rainbow and disappears into the sky. One of the hunters throws a bola at him, but to no avail. It is lost in the sky and becomes the Belt of Orion. During his flight, Kakn stamps his foot in the sky, creating the constellation Crux. According to the story, Kakn runs through the firmament to this day.

An emu in the Australian sky

From ostriches, it’s a small step to emus, as some First Nations people in Australia see Crux as an emu’s footprint. Omnipresent in Australian Aboriginal cosmology is the interpretation of the ‘Emu in the sky’. Unlike in western constellations, the emu is not only made up of stars, but mostly of the dark nebulae between them. The head of the emu, for instance, is the Coalsack nebula, while its legs extend into the constellation we call Scorpius. Some stories mention Crux as a crown on its head.

For the Wiradjuri people, the emu is called Gugurmin, and moves around the sky. Based on its position, the people would know what season it is and when it is the time to collect emu eggs. Through oral tradition, this knowledge was carried over to the next generations, for thousands of years.

Stingrays, sharks and crocodiles

Australian Aboriginal cosmology also has lots of other stories featuring the Southern Cross. To the Ngarrindjeri people, Crux is the stingray Nunganari and the Pointers are sharks.

For others, Crux is the footprint of a giant wedge-tailed eagle, with the pointer stars as a throwing stick used to hunt it. The Kaurna people, just like the Ngadjuri, Nukunu and Adnyamathanha peoples, see the cross as the foot or the claw of the eagle. To others still, it is a friendly crocodile.

The Boorong people see a ring-tailed possum, called Bunya, at the top of the tree, formed by the Cross. The two smaller stars above the top star are its eyes or ears, and its tail changes position as the constellation moves. The story goes that Bunya was a man who ran away from the evil emu Tchingal (yes, him again) and hid in a tree for so long that he turned into a possum.

Tagai, standing on his canoe

Continuing in Australia, the Torres Strait Islander peoples have a constellation known as Tagai. A great fisherman, Tagai goes fishing with his crew of 12 spirit beings, who take on human form on Earth. It is a very hot day, and the crew uses up all his drinking water, enraging Tagai. He kills their human form, and returns the twelve to the sky: six to Usal (the Pleiades) and six to Utimal (Orion).

Tagai himself can be seen in the sky standing in his canoe. The Southern Cross is his left hand, holding a spear. When Tagai’s left hand dips into the sea, the Islanders know the wet season (Kuki) is about to begin. The stars guide the Torres Strait Islanders in many other ways, too: they indicate when to plant their gardens or when to hunt turtles and dugongs, a mammal related to the manatee. Like astronomy still does today, these stories helped people understand the patterns in the world around them.

The disappointment of Mark Twain

Let’s wrap up with the words from the American author Mark Twain. In his travelogue Following the equator; a journey around the world, he is not impressed when he sees the Southern Cross for the first time: “Judging by the size of the talk which the Southern Cross had made, I supposed it would need a sky all to itself. But that was a mistake.”

To Twain, the cross interpretation seems a bit far-fetched: “It does after a fashion suggest a cross — a cross that is out of repair — or out of drawing; not correctly shaped.”

So maybe the emu or the canoe anchor are more inspiring interpretations after all? Whatever we may see, be it an ostrich, a cross or alpha, beta, gamma and delta Crucis, they have one thing in common: they all help us, humans, understand the Universe a little bit better. So, when you can, take a look at the sky, find Crux and think of all the stories these stars have given birth to. Hopefully, you will not be disappointed.

Notes

[1] Taken from https://maoridictionary.co.nz/word/3522 (accessed 24 September 2024)

Links

- Borba, M., 2019, ‘The Brazilian Flag and The Southern Cross’, Harding University

- Hamacher, D. “A shark in the stars: astronomy and culture in the Torres Strait” at https://theconversation.com/a-shark-in-the-stars-astronomy-and-culture-in-the-torres-strait-15850

- Hamacher, D. “Look up! There's an emu in the sky” (accessed 24 September 2024)

- Moré, L., 2000, “La Caza del Avestruz”, Revista Nordeste 2da. Época N11

- Needham, L., 2021, ‘The symbolism of Australia’s Southern Cross’, University of Melbourne

- Pozo Menares, G. & Canio Llanquinao, M., 2016, Wenumapu : astronomía y cosmología mapuche, p 90.

- Pring, A., 2002, ‘Astronomy and Australian indigenous people’

- Twain, M., Following the equator; a journey around the world, 1897, p 79-80, https://archive.org/details/followingequator00twaiuoft/page/78/mode/2up?view=theater (accessed 25 September 2024)

- Walters, R., Buckley, H., Jacomb, C., Matisoo-Smith, E., 2017, ‘Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand’, Journal of World Prehistory. 30 (4): p 351–376.

- Wassilieff, M., 'Southern Cross', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/southern-cross (accessed 14 August 2024)

- “Tāwera, Te Aramahiti – The Morning Star Guides Eastward: Reviving Traditional Navigation Knowledge in the Pacific”

- https://www.assa.org.au/resources/aboriginal-astronomy/eagle-dreaming/

- https://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/endeavour-voyage/sky-stories

- https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/622-the-star-compass-kapehu-whetu

- https://www.eso.org/public/teles-instr/paranal-observatory/vlt/vlt-names/melipal/

- https://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/defining-symbols-australia/southern-cross

- https://www.pmc.gov.au/resources/australian-symbols-booklet/national-symbols/australian-national-flag

- https://chileprecolombino.cl/en/arte/narraciones-indigenas/tehuelche/la-cruz-del-sur/

Biography Hanna Huysegoms

After nine years of professionally talking and writing about books, Hanna wanted to dip her toe in other waters. The ESO telescopes piqued her curiosity, bringing back memories of her 10-year-old self, buried with her nose in astronomy books. As it turns out, the leap from writing about medieval manuscripts to writing about stars and exoplanets is not that big. Born and raised in Belgium, Hanna studied English and is passionate about accessible and easy-to-understand language in all domains.