Discovering the First Interstellar Asteroid

Olivier Hainaut tells us about a visitor from outside our Solar System

- The story of the discovery of the first interstellar asteroid

- How ESO’s telescopes are used to make rapid follow-up observations

- The process behind new and exciting scientific discoveries

Q: Tell us about how it all began. At what moment did you realise this was such an exciting discovery?

A: It all started with a short and cryptic email from my long-time friend and collaborator from Hawaii, Karen Meech, with “URGENT’’ in the subject line, telegraphic style. The main text was filled with words like discovery and immediate follow-up. Needless to say, I called her — the 12 hour time difference between Hawaii and Germany is not that bad, especially as Karen is a very early morning person and I tend to be more of an evening guy. Karen was jumping up and down: our friends at the Pan-STARRS telescope had discovered a moving object. This happens every night — Pan-STARRS discovers many comets and asteroids — but its orbit was found to be hyperbolic, which had never happened before. This meant that the object is not orbiting the Sun. We already knew a few comets with just barely hyperbolic orbits, probably caused by interactions with planets or the jet-like effect of the cometary activity, but apart from these exceptions, all known comets and asteroids are bound to the Sun and orbit around it on elliptical paths. All except this one.

That definitely deserved the “URGENT” email: this object is zooming past the Sun and heading away from the Solar System, forever — and fast.

Q: After the initial discovery, what was the next step?

A: The next day, we slammed together a request for telescope time to observe the object while we could. Normally, these requests have to be written six months to a year in advance, but fortunately there’s a super-fast-track way to apply for time in emergency cases. The request was submitted to ESO, reviewed by other astronomers (who became almost as enthusiastic as us!), and the director approved it — all within just a few hours.

In the meantime, I’d already started to prepare the observations — that is, to define all possible details of the exact sequence of images we needed, taking into account that the object is moving very fast in the sky. As soon as I was notified that we’d been allocated telescope time (a few hours on UT1, one of the Very Large Telescope’s 8.2-m telescopes), I uploaded the observation definitions to the telescope database. That night, my colleagues working at the Paranal Observatory performed the observations and quickly sent the images to Germany, where I looked at them in the morning.

Q: So what did the images show?

A: Images coming straight from the telescope are not pretty. Not only are they in greyscale (the beautiful images of space you are used to seeing are assembled from various greyscale images obtained through colour filters), but they also have all kinds of odd features produced by the camera that need to be corrected. I spent the morning processing the images, which were excellent. First conclusion — this is not a comet!

We have been expecting interstellar objects for many years — we know that our Solar System has been ejecting comets and asteroids into interstellar space for the past 4.5 billion years. If our neighbouring stellar systems do the same, interstellar space should be full of these objects, so we believed it would be just a matter of time before we bumped into one. Except that most of these interstellar objects should be comets, and comets are much easier to spot than asteroids, so we had expected to first spot an interstellar comet! The object we discovered was most definitely not a comet: it didn’t have the faintest hint of dust around it, as would be expected. Combining all our data from the Very Large Telescope (VLT) observations, we produced a very deep image, from which I measured that there is less than a gram (!) of dust in each pixel around the object.

Q: What were you thinking when you realised this object wasn’t a comet?

A: At that stage, it was impossible not to draw parallels with the great sci-fi novel “Rendezvous with Rama” by A. C. Clarke, in which astronomers discover an object in a hyperbolic orbit crossing the Solar System — and it is not a comet. In the book, the object’s brightness is extremely stable, but because asteroids normally have irregular shapes, they appear brighter and dimmer as they rotate, alternately exposing their larger and smaller sides to us. So a constant brightness is not normal; in the novel, the object turns out to be a giant starship, which the heroes go on to explore. Reality was quite different.

Q: How so? What did you find out about the object?

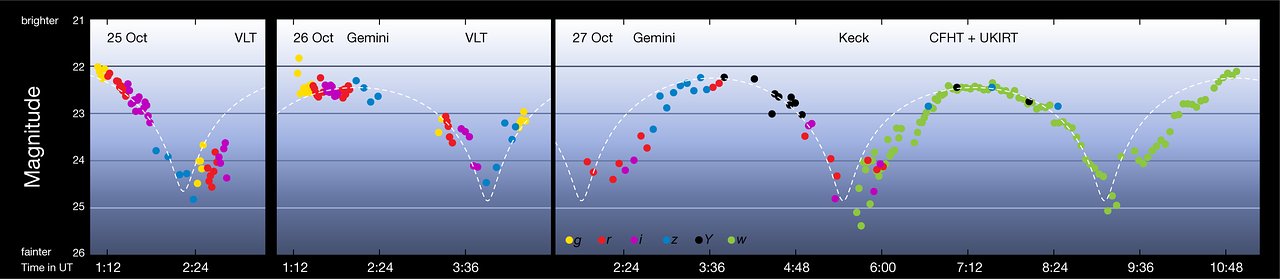

A: As we collected more data with the VLT, in conjunction with Gemini (another 8-m telescope) and the Canada-France-Hawaii telescope (a “small” 3.6-m telescope), we realised the brightness of our interstellar object was varying a lot. Actually, by a factor of 10, which is close to an absolute record.

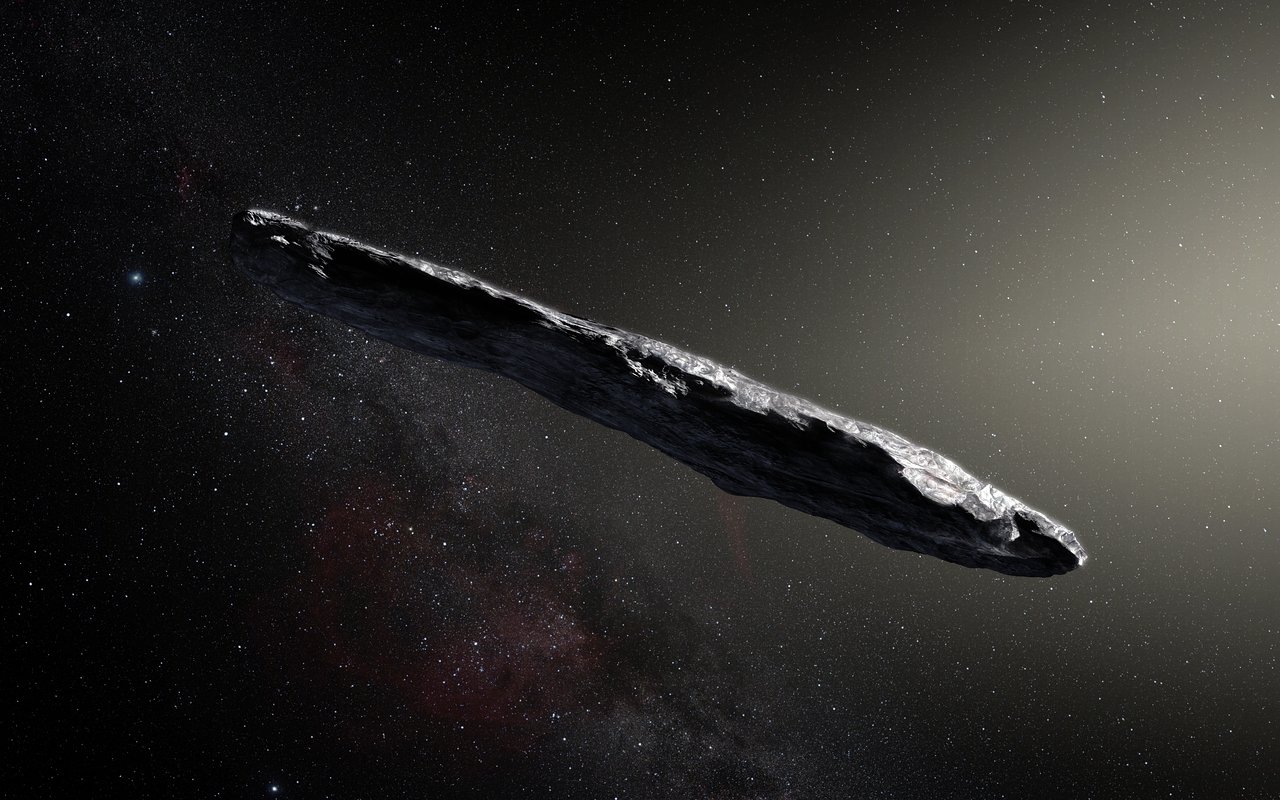

The lightcurve of the object (the variation of brightness with time) gave us a lot of information. Firstly, we found the rotation period to be 7.3 hours, which is fairly standard for an asteroid. Secondly, while we don’t know the exact shape, we can infer that its “large” side is at least 10 times longer than its “small” side. We don’t know how thick the asteroid is, but we can guess using good old basic physics: as the lightcurve is nice and regular, the object must be gently rotating and not tumbling uncontrollably. This implies it is rotating around its smallest dimension, as demonstrated by Euler in the eighteenth century, so we’re dealing with a long cigar-shaped object, twirling like a cheerleader’s baton.

By measuring the amount of sunlight reflected by the object, it is also possible to make educated guesses about its length, depending on the darkness of the surface. In this case, our object is a few hundred metres long. Knowing the size and the rotation period, we computed the centrifugal force at the tip of the asteroid and estimated the strength of gravity on the surface. It turns out that if you were to stand on the tip of the spinning asteroid, you’d be ejected in space: the centrifugal force is stronger than the gravity! This, in turn, implies that the object is one solid piece of rock.

Finally, as we observed the object through different colour filters we measured that its surface is reddish, like the surface of some “old” asteroids and comets in our own Solar System.

So the first interstellar object crossing the Solar System is full of surprises: it is not comet, it’s a solid piece of rock with an extreme shape! But at least its surface is familiar-looking. This suggests that the interstellar object is not that exotic: asteroids in our Solar System and in other solar systems have things in common.

Q: Now that you’ve discovered and characterised the asteroid, what’s next?

A: We’re going to keep observing it for as long as we can, using the VLT and the Hubble Space Telescope, but by the end of the year, it will be too far from us and from the Sun and therefore too faint to be observed. Forever. Unless we send a send a spacecraft after it...

Numbers in this article

| 1 | Number of known interstellar asteroids (as of 15 Nov 2017) |

| 948 | Number of known comets (as of 15 Nov 2017) |

| 746324 |

Number of known asteroids (as of 15 Nov 2017) |

Biography Olivier Hainaut

Olivier Hainaut is an astronomer working on comets and asteroids. He has previously worked at ESO’s Paranal Observatory, and before that at the La Silla Observatory, but is now back at ESO Headquarters in Germany. Email: ohainaut@eso.org