- What motivated some women at ESO to pursue a career in STEM

- What their current STEM roles are, and the path they took to get there

- Some of the challenges they faced along the way and solutions for the future

A career in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) can be an incredibly rewarding path to take. There are many different twists and turns within the sector, and not everyone necessarily follows the traditional route into academia. To honour the International Day of Women and Girls in Science celebrated today, we have interviewed several women in diverse roles at ESO about their career paths, how the industry has changed over their time working in it and how we can retain more women in STEM roles. This post is the first of a two-part series, where we will hear from five of them.

“Where do we come from? Are we alone? What is the world made from?”

What bonds many scientists and science enthusiasts is the natural curiosity to learn more about the Universe we live in. And our interviewees are no exception. This inquisitiveness has often led them down unexpected and interesting paths throughout their careers.

“I have always been interested in nature,” recalls Linda Schmidtobreick, ESO staff astronomer and Deputy Head of the Office for Science in Chile, as she explains her route into astronomy. “I actually studied to become a teacher but once I got my teaching degree, with a thesis on an astronomic topic, my supervisor suggested that I continue with a PhD in that research. Although I sometimes miss teaching, that got me hooked and I continued with my career as an astronomer.” She now combines her research on variable stars with duties at Paranal Observatory, home to ESO’s Very Large Telescope.

“I actually wanted to become a comic book designer,” says Julia Seidel, an ESO fellow in Chile studying the atmospheres of exoplanets, “but the draw to physics was too strong, so I decided to study physics with a focus on nuclear physics and worked at CERN. I realised my academic studies weren’t over yet so I went back to university to study atmospheric physics. On a whim, I sat in a public lecture on the atmospheres of exoplanets and was immediately hooked.”

Francesca Fragkoudi, an ESO fellow in Garching researching how galaxies form and evolve, followed a “relatively standard career path” as she completed both her undergraduate and masters degree in physics and astronomy. But this was not the only area of physics she considered. “I also briefly flirted with the idea of pursuing a PhD in climate science,” she continues, “but the mysteries of the Universe pulled me back to the field of Astrophysics.”

“My career journey has been somewhat serendipitous,” says Tania Johnson, Head of the ESO Supernova Planetarium & Visitor Centre, as she explains where her love of public engagement came from. “After graduating, I worked as an analytical chemist for a year, but knew that wasn’t for me long-term. I started to look into PhD options and came across an advert for a Science Communicator job. I had no idea what to expect but figured it could be something for me. And I was right!”

We also talked to Liz Humphreys, Head of the Department of Science Operations at ALMA, an array of radio telescopes in northern Chile of which ESO is a partner. Liz also began her academic journey with a chemistry degree which she knew she did not want to continue with. “I was fairly seriously planning to pursue a career in law after my degree,” she recalls. “However, by chance, I got a summer job after my Chemistry degree inputting data for an astrophysics group in the university. I really liked it, and they offered me a PhD position, so I stayed and the rest is history! “

If they can see it, they can be it

Recently, there have been major advancements in improving gender balance within the sciences. However, there is still a lack of women in senior positions throughout research and academia. As you move up the academic ladder, progress drastically slows down, according to She Figures 2018 data. In the European Union, women researchers hold only 15% of equivalent full professor academic positions, despite female doctoral students and graduates making up almost 40% of the total population.

“Women have to deal with the impact of sub-conscious bias which could prevent them from being promoted or even considered for some roles,” Liz explains.

It is undeniable that representation has a huge beneficial impact on increasing diversity, but with the lack of women in higher educational roles, not everyone is fortunate to have a woman role model. Therefore, women, including our interviewees, have regularly had to look to their direct colleagues or those outside of the STEM community for mentorship and community.

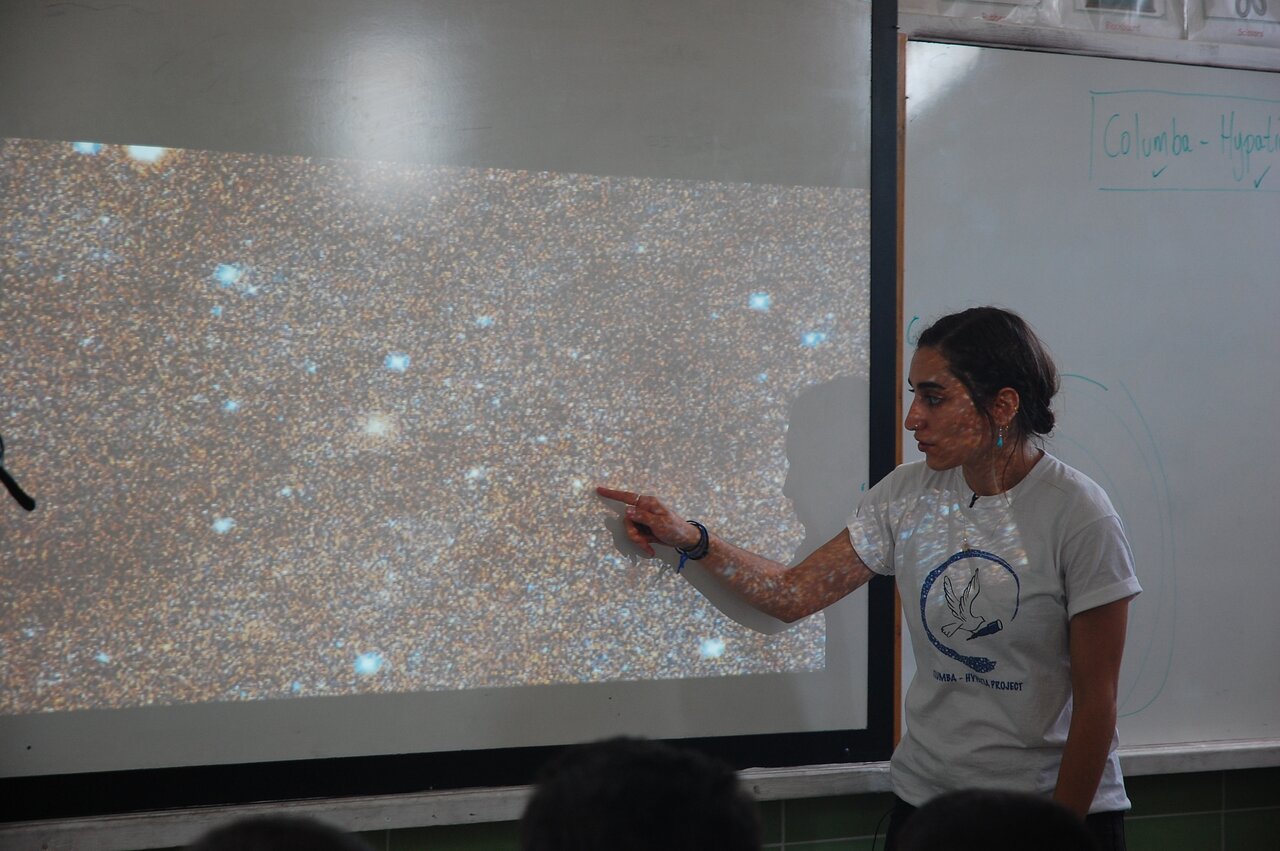

“The stronger exposure of young women and girls to role models makes them realise despite the stereotypes that STEM is a possible career path for them,” Julia explains.

“I can’t say that I had a STEM mentor,” Francesca shares, “but I was lucky enough to be raised by a single mother, who is a strong, independent woman, unafraid to carve her own path and speak her mind. She supported and encouraged me to be myself and inspired me to follow my dreams, and made me feel that pursuing a career in STEM was possible.”

“I didn’t have any role models that I really related to until a few years ago,” Liz reminisces. “It was quite strange for me to realise then that there were now women in visible roles who I might want to try to emulate. So that has been very encouraging to me, as a sign that things are changing.”

Both Linda and Julia agree with this sentiment, sharing that their first real mentors in STEM were their own peers or professors who encouraged them and created a sense of community and support in their department. Tania experienced something similar in her first roles. When asked specifically about science communication, she said that “there are various women of a similar age whom I really admire and aspire to become like them. But the science communication sector typically has a better gender balance, is generally a very supportive community and it’s not very unusual to see women in positions of responsibility.”

“During my last ten years of studies and working in STEM, representation has gotten better,” Julia explains. “However, the day-to-day bias and micro-aggressions have remained, ultimately pushing women out of the field before they reach leadership roles.”

Duty of Care

Astronomical research can open the keys to some of the greatest mysteries in our cosmos but it can come at some costs. In particular, having to work on shifts in remote locations can particularly impact those who have caring responsibilities and, unfortunately, it is historically and systemically women who often take up these roles.

“Child and elderly care remain mainly pushed on women in society, which makes a high stakes career much more challenging to navigate,” Julia explains.

“Working in the observatory, it is very difficult for a woman to have a child and keep working, with shifts of one to two weeks where you are away from home,” Linda expands on her experience as a support astronomer. “There is a lot of infrastructure still missing to make the work environment friendly for mothers.”

The expectation of motherhood and caregiving is extremely outdated and can often lead to unconscious bias resulting in women not entering certain roles or being promoted. As Tania explains, “the system is still set up in an old-fashioned way: the man goes to work, the woman stays home to look after the children. But that’s not how modern society is – there are lots of different family constellations: single parents, same-sex couples, adoption or fostering, couples who are not married...”

“In many relationships, both parents would like the opportunity to spend time with their children and not have that negatively impact their career development,” Tania continues. “As long as there are these long-standing systemic issues, it is hard to change attitudes and cultures.”

Taking a Global Perspective

“Physics wasn’t something that girls in Cyprus were encouraged to pursue when I was growing up,” Francesca shares. This is not an uncommon experience. A study by ESO’s Francesca Primas found that the progression of balance between the genders in STEM can result in disparities of as much as a 20-30% difference across different countries.

Through a career in astronomy, there is the opportunity to live in many countries depending on where your research takes you. Many of our interviewees have lived in several countries and have seen first hand the differences in gender balance. “My perception is that the sector is becoming more diverse and inclusive everywhere over time, but the approach and speed with which this is happening can be quite different,” Liz remarks.

Linda agrees and reflects on her experiences in different institutions. “In Bochum, we were three women among more than 100 students in our year, whereas in Padova there were many female astronomers. And at ESO and the Chilean universities there are a lot of female scientists. I was very surprised to see that.”

Why do we need diversity?

Some of the greatest scientific discoveries have resulted from people thinking out of the box. This requires a large amount of creativity and innovation, something that should not be limited to a certain gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, social background, etc. Therefore, having a diverse and inclusive team directly increases scientific progression.

“A world without diversity would be boring, for a start,” says Tania. “STEM needs different minds looking at things in different ways. Being presented with diverse viewpoints pushes development and broadens the scope for innovation.”

Francesca agrees stating that “science is a creative and collaborative endeavour, and the more diverse perspectives we have, the more creative, innovative and groundbreaking our science will be.”

How do we promote women to enter the sector and retain them?

“More than ever I believe in the importance of developing hiring and retention policies which mean that diverse, qualified candidates get hired into organisations and, once there, are fully included and want to stay,” states Liz, who also chairs the Respect, Diversity and Inclusion Working Group at ALMA. “Without this, we risk missing out on getting very talented people into STEM workplaces and will be less effective as organisations as a result.”

Julia agrees with the need for training, not just through the hiring process but in the earlier stages of career development. “There needs to be training of people in power at the university level, professors, deans, administration. That means everything from how to write reference letters for women, how to write manuals in gender neutral language, all the way to unconscious bias training. These people hold the key to retaining the current talent all the way to the top.”

Furthermore, the voices of women should be amplified in the discussions of how to improve the work environment.“There is no quick fix,” Francesca agrees, “but if we are to improve women’s experiences in STEM, we first need to ask women what would help them, listen, and then implement the necessary changes.”

As Linda says,“hiring more women also helps because you can more easily discuss such problems and help each other in meetings and conversations when mansplaining or manterrupting happens.” She is optimistic about this: “I must say that this has improved in the last years; either we have better managers or also men are more sensitive to these issues.”

“There is a new generation coming with improved views on diversity and equality,” Tania remarks. “If we can continue to nourish and enable them, give them the skills and tools they need, I’m optimistic that the landscape will look better for all.”

ESO is continuously looking for ways to address diversity and inclusion in a broader sense, for example by conducting reviews of procedures including the recruitment and career development process to ensure it is as unbiased as possible. Recently, ESO has achieved gender balance in the composition of panels that evaluate observing proposals for the telescopes, and the proposals are now judged anonymously to minimise systematic biases. ESO is also preparing a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Plan to help attract a more diverse workforce and continue promoting an enabling environment for all, and in particular for women.

Keep your eyes peeled for the second part of this blog post coming next Friday, where we’ll hear the career trajectories from even more women in STEM roles within ESO, including instrumentation, software development, and more!

Note that all images in this blog post are copyright of their respective owners, as mentioned in the credits, and are not released under our usual CC-BY license.

Biography Juliet Hannay

Juliet Hannay is part of the science communications team at ESO. She is a former student of the University of Glasgow acquiring a Bachelors and Masters degree in Astronomy and Physics. Juliet found a passion for science outreach and communication through her roles as Outreach Convenor, Vice President and President for the Women in STEM society and specialist editor for the Glasgow Insight into Science and Technology magazine.