- What should we look for in an exoplanet to find life?

- Why we may need to refine the meaning of ‘habitable zone’

- How much do we know about the habitable exoplanets discovered by ESO?

The idea of finding life on other planets has captivated humanity for centuries. As we find more and more potentially ‘habitable’ exoplanets, is it time to refine what we consider habitable? From our most pessimistic to our most optimistic view of the Universe, we explore how close astronomers are to finding a new Earth.

Understanding the habitable zone

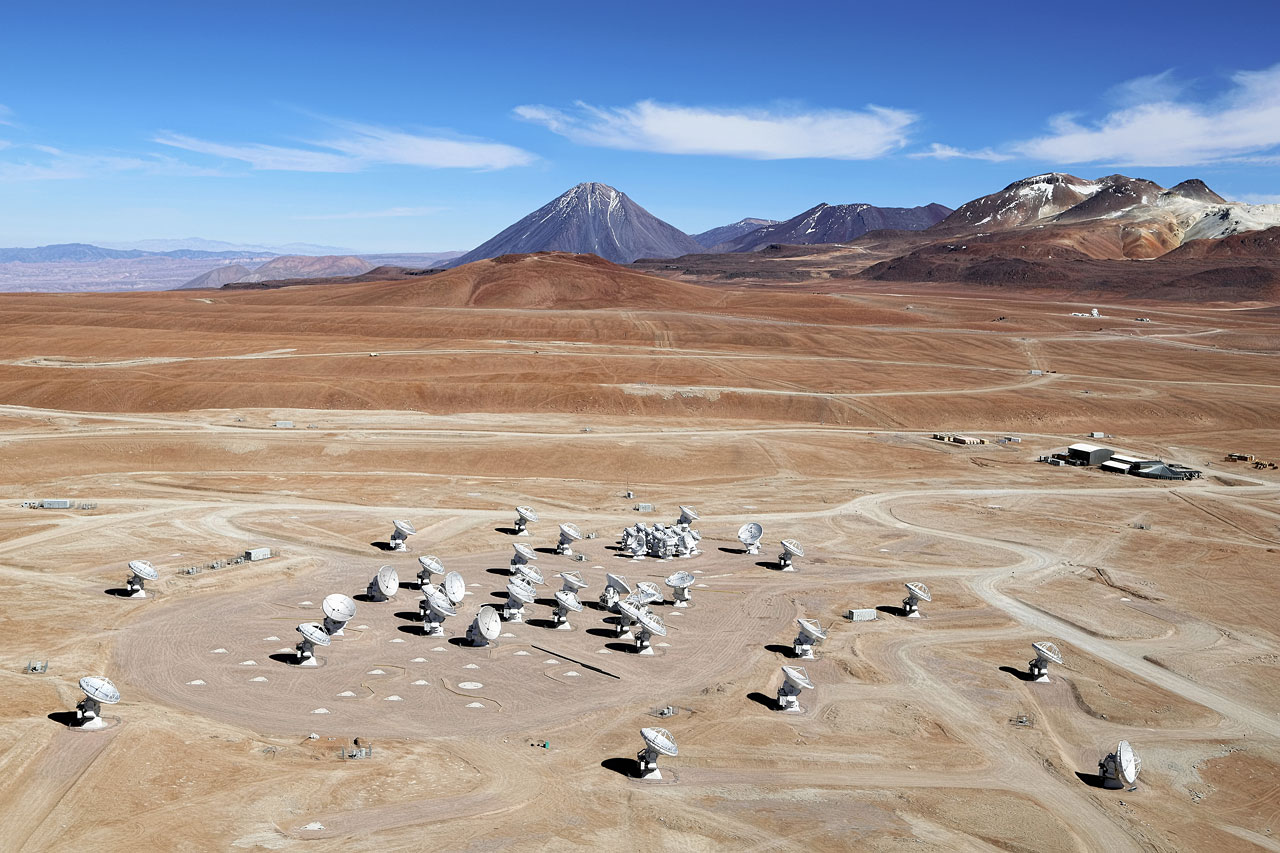

We discover new exoplanets every year. What used to be an incredible achievement 30 or even 20 years ago, is now almost routine. We have discovered over 6000 planets orbiting stars other than the Sun, at least 330 of them by ESO telescopes at La Silla and Paranal observatories.

What astronomers and the public alike dream of confirming on one of these planets is what’s considered to be a key ingredient for life: stable liquid water at the planet’s surface.

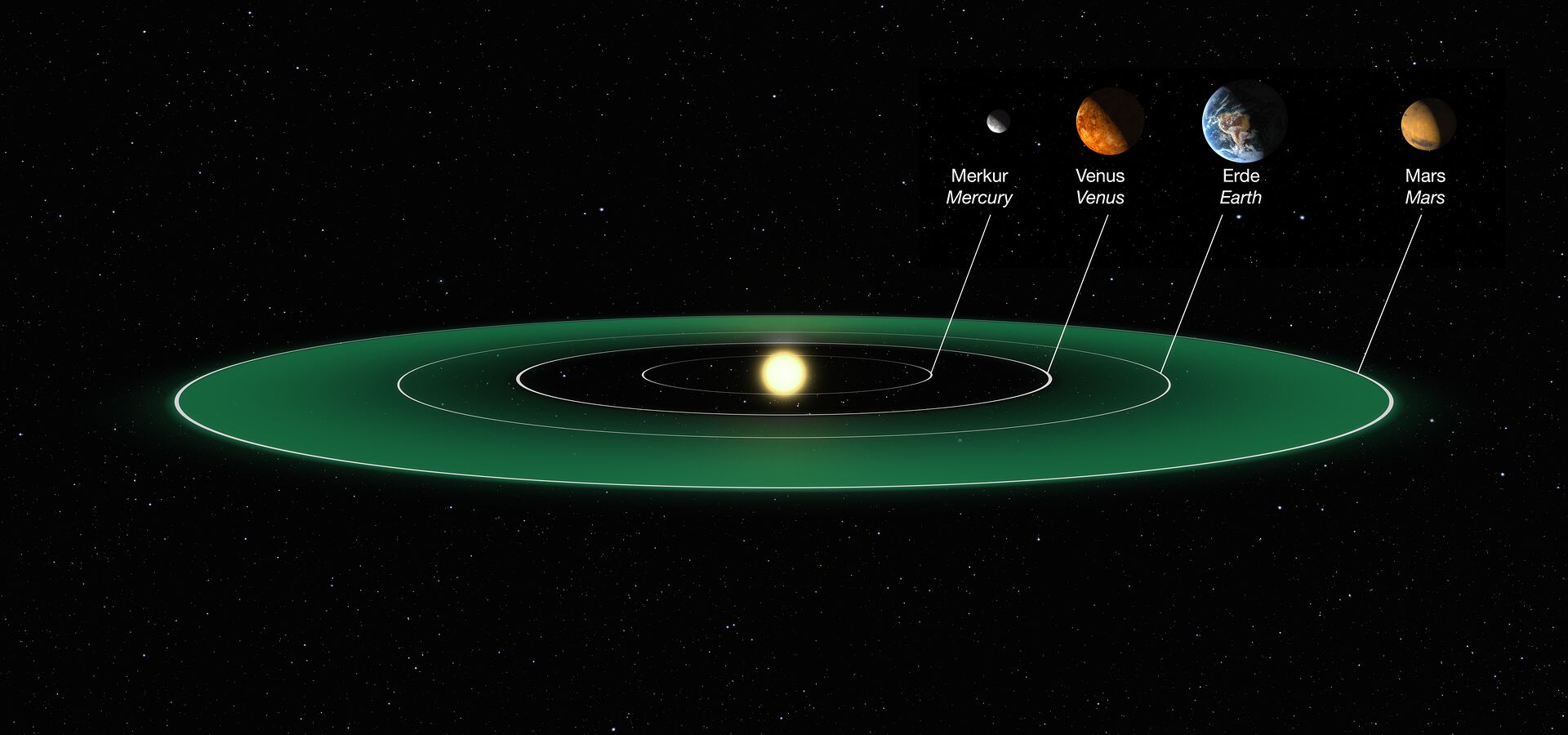

For surface water to be in a liquid state, an exoplanet cannot be too far from (too cold) nor too close to (too hot) from its host star. It has to orbit in a temperate zone known as the ‘habitable circumstellar zone’ or simply ‘habitable zone’. As stars come in different types, sizes and masses, each star has its distinct habitable zone.

Telescopes around the world have found some 70 exoplanets in the habitable zone of stars, but only about 30 would be rocky ones like Earth, where oceans could exist. This, however, does not mean finding life there is guaranteed. For example, planets like Venus or Mars orbit within the limits of the Sun's habitable zone, but finding life there looks very improbable. What else do we need for a planet to be truly habitable?

The right amount of despair: is the habitable zone enough?

Even when a planet is in the habitable zone, its surface temperature may not always be as ‘temperate’ as we would like.

Planet HD 20794 d, for example, is a ‘Super-Earth’ located 20 light-years away. It was discovered in January 2025 thanks to a combination of instruments at ESO’s Very Large Telescope and the ESO 3.6-metre telescope. The orbit of this planet, though, is so elliptical that the planet moves out of the habitable zone throughout its year, leading to an extremely long ‘winter’ that is not very welcoming to life, to say the least.

But even with a perfect orbit, temperature may not be pleasant. In 2013, astronomers used the ESO 3.6-metre telescope to find three planets in the system Gliese 667C, located 22 light-years away, all of them well within the habitable zone. Since then, we have discovered that Gliese 667Cf is tidally locked: despite rotating, one of its sides always ends up facing the star, leaving it scorched, while its other side remains in permanent shade and cold. There, life as we know it could only prosper in an area between the bright or dark sides, or if wind currents spread heat evenly across the planet.

Truly habitable planets should also have a magnetic field and atmosphere that protects life from cosmic rays, including those coming from the host star. In 2016, astronomers using the TRAPPIST telescope at ESO’s La Silla observatory discovered three planets in the habitable zone of the ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST 1. Since then, we have learned that planet TRAPPIST1b is not only tidally locked, heavily radiated, but also has no trace of an atmosphere — not the best place for life to be. It is unknown if the other two planets have an atmosphere capable of stopping the radiation from their star.

Radiation is also one of the threats of planets orbiting M-type stars, the most common stars in the Universe. M-types have habitable zones very close to their cool surfaces, which leave planets exposed to the strong solar flares often produced by these heavily active stars. Proxima Centauri b, our closest potential second home outside of the Solar System, orbits such a star. This exoplanet does not cross in front of its host star from our point of view, so we don’t see the star’s light traversing the planet's atmosphere, preventing us from easily revealing its composition.

Even when planets have circular orbits in the habitable zone and an atmosphere, an exoplanet can still be a hellscape — just look at our neighbour Venus. In fact, life on Earth would not have been possible without many of our planet’s features: from plate tectonics providing energy and nutrients to the age of our Sun, old enough for a planet to have sufficient time to develop life, but not so old that the star is in a stable phase of its life, with plenty of time ahead for life to flourish. Some may wonder, then, if Earth is just very special.

A glimpse of hope: opening ourselves to new possibilities

In 2007, ESO discovered the habitable planet Gliese 581c. As it was one of the first habitable planets ever found, and only 22 light-years from us, astronomers were brimming with excitement. Later measurements found that the exoplanet is at the very inner edge of its habitable zone and is therefore probably very hot. Is there any hope for Gliese 581c?

If Earth has taught us something, it is that life is extremely resilient. On our planet, life has been found in unimaginable places: in the depths of the oceans, in boiling hot springs, deep underground, in acid waters… These organisms, most of them bacteria or archaea, are extremophiles that could easily call Gliese 581c or similar planets, home.

In fact, many sites on Earth are not the easiest to live in. Freezing areas in the North or South Pole have no native fauna or flora and in the driest parts of some of the world’s deserts, like the Atacama, life can also struggle to thrive. This raises the question: could something better than Earth exist? Some researchers think that a habitable planet with smaller continents, larger areas of shallow oceans and slightly warmer temperatures could provide even better conditions than Earth for life to thrive and evolve.

If we are open to possibilities, life could be found even outside of the habitable zone. Jupiter’s gravity, for example, is so strong that it heats up its satellite Europa, allowing oceans of liquid water to exist even at such a far distance from the Sun, albeit beneath the moon’s icy crust rather than at its surface.

We could even imagine life-forms completely different to ours, living in oceans of ammonia and made of molecules we have never seen before, able to inhabit places very different from Earth.

Earth remains our only example of a habitable planet, so we may have to restrict our search to familiar-looking organisms and exoplanets, for the moment.

New efforts beyond the habitable zone

Beyond finding planets in the habitable zone, astronomers are now focusing their efforts into detecting life-related elements. Gases like CO2 and methane can be produced through biological processes, but not necessarily so. Other gases like dimethyl sulfide are thought to be exclusively produced by living organisms — though not everyone agrees that it can be considered a reliable biosignature. This is a key problem: how does one confidently prove that a given spectral signature is not caused by non-biological processes?

Future facilities, like ESO’s upcoming Extremely Large Telescope, promise richer data for exobiology research. It will not only help us find more planets in the temperate zone of their stars but will also help reveal the traits that will tell us if they are truly habitable. But we need to stay alert when interpreting the data, as habitability does not guarantee that a planet actually hosts life.

Biography Alejandro Izquierdo López

Alejandro is an evolutionary biologist from Spain who has been researching the ancestors of shrimps, centipedes and insects, trying to understand how evolution worked 500 million years ago. He has discovered several strange-looking extinct animals such as the “Pac-man crab” Pakucaris or the “Cambrian-beagle” Balhuticaris. He also loves communicating any type of science, including (of course), astronomy. At ESO, he aims to strengthen his communication skills while re-igniting his childhood passion for the cosmos.