In conversation with Catherine Cesarsky:

the former ESO Director General talks new projects, leadership and future scientific advances

- How Catherine’s different leadership roles have shaped her perspective of science.

- What were Catherine’s most memorable moments as Director General of ESO.

- What Catherine is most looking forward to in the future of astronomy.

Q: When did you realise that science, and particularly astronomy, was what you wanted to pursue?

A. I hear a lot of people saying how astronomy has been their main interest since childhood, but that wasn’t the case for me. I grew up in an environment extremely far from science. My father had a bookstore and there were walls of books on literature and art all over my house, but not one was related to science.

I went to a French school in Argentina and spoke French at home, so it was easy for me to be good at literature and to write essays in French. However, I really enjoyed the challenge of maths and physics. I was about fourteen years old when I started thinking about where I wanted to go to university. The question was, what did I want to study? When I decided to stay in Argentina, I went to the School of Engineering at Buenos Aires University with a friend of mine, to put our names down for the entrance examination. The guy taking names looked at me and said, “Are you sure? There are no women here.” So I left — I don’t regret not studying engineering.

I then enrolled in the School of Exact and Natural Sciences within the same university. I couldn’t choose between studying physics and maths, so in my first year I studied both before choosing physics in my second year. In my fourth year of university, we had to select the subject of our Master’s thesis, and this same year, a new professor arrived: an astrophysicist. I immediately thought this topic would be interesting and I said I would like to work with him, as did several of my friends. That’s how I got into astrophysics: the minute I started I knew that was it. I have loved it all my life since then.

Q. What keeps you excited and makes you want to start working in the morning?

A. I don’t think there is a single day where I don’t look at something related to science, even on weekends. Most of my career has been near Paris, at CEA Saclay where there is a very good astrophysics group that I have been involved with since 1974.

Throughout the last year, working groups in my laboratory, focused on different astronomical instruments and research areas, are still meeting but now online. There are a lot of lectures and discussions that I participate in and I always have a question to ask. Not a week goes by where I don’t find something completely fascinating happening in our field.

Q: What are you doing currently? Do you still have opportunities to engage with research directly?

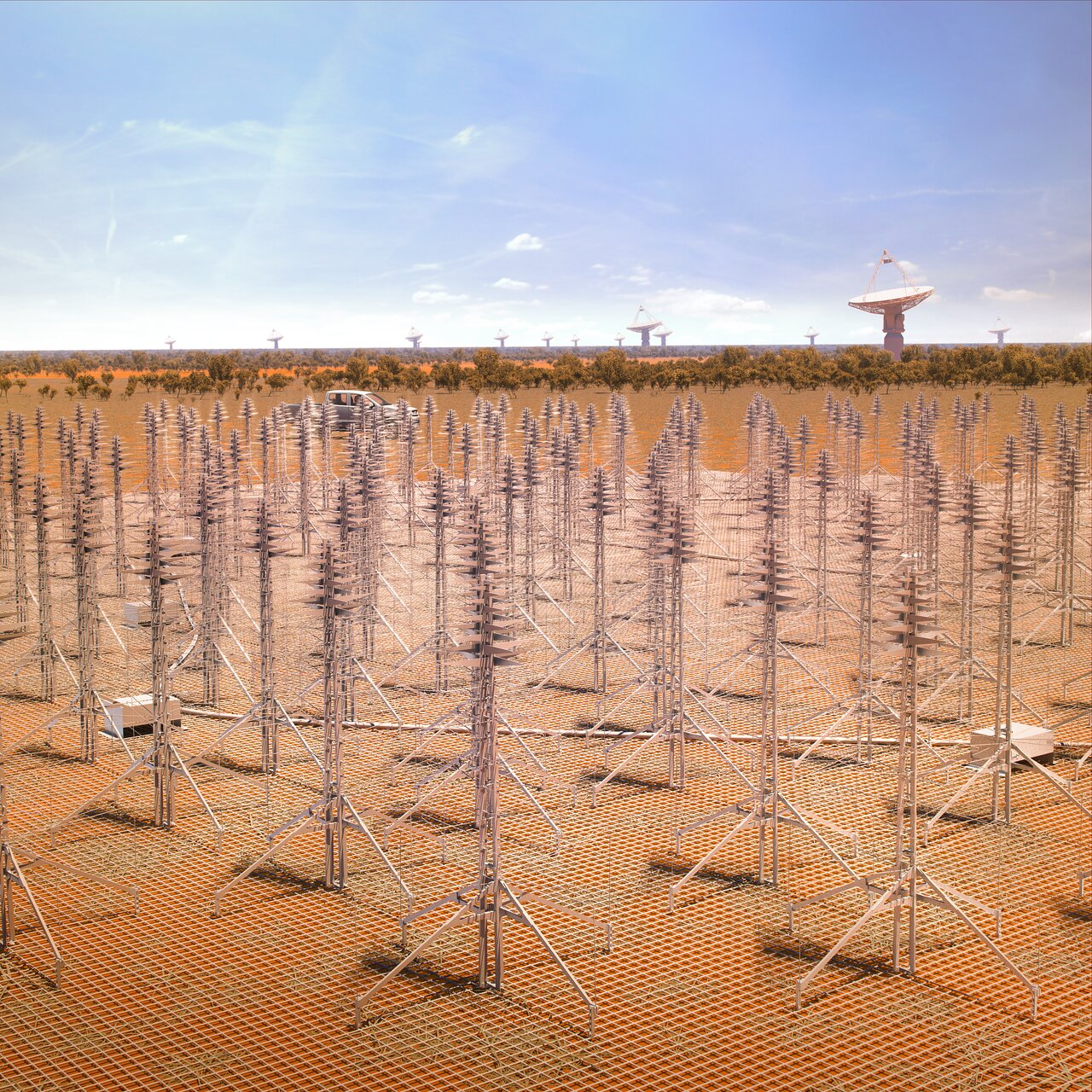

A. At the moment, I am heavily involved in the development of SKA, the Square Kilometer Array project. (Editor's note: SKA is an international effort to build the world’s largest radio telescope. Located across South Africa and Western Australia, it will eventually combine several thousand dishes, 15 metres in diameter, and up to a million low frequency antennas.) In 2006, as ESO Director General, I co-organised a symposium about future large facilities, such as the Extremely Large Telescope, SKA and the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST. Of course, I was there promoting the ELT, but even at the time I felt SKA was absolutely necessary as well. Astronomy needs multi-wavelength studies more and more and any problem you are researching in astrophysics can progress if there is a high-performance radio facility.

I was surprised in 2017 when I was invited to chair the board of SKA Organisation. I accepted and was in this role until four weeks ago, when I became chair of the SKA Council for the newly created SKA Observatory. In this time, the SKA Organisation prepared, and has now published, the plan for how SKA will be constructed and set up the premises of SKA Observatory, the intergovernmental organisation with six member countries and ten prospective members at various stages of joining. It was very different to when I became ESO Director General as then everything was already set up for me to take over from the previous director. However, it’s very exciting for me to use what I have learned throughout my career to help put together a big international project that I consider worthwhile.

Aside from my involvement in SKA, I do a lot of evaluations or advising of projects and of laboratories or institutes, and selecting recipients of prizes or grants. I still sometimes give advice on a political level because of my political past. All this takes up quite a bit of my time but is rewarding as every time I learn something new.

Q: You’ve been in several prestigious leadership roles throughout your career. How have these different roles shaped your perspective of science?

A. It has helped me realise the many different ways that people can participate in science, and how all of these ways are equally important.

I started out as a theorist, about the same time that computers were becoming important. I like to work at night, so I imagined myself spending nights at home having wonderful ideas and solving equations. I was lucky to have had that experience, spending a good 15 years of my career this way. I could easily have stayed a theorist all my life and thought this is the only “real” way to do science. However, my theoretical work plunged me into work on space instruments, both high-energy and infrared, and eventually to ESO and overseeing ground-based instruments and observations. I realised you need all these components: theoretical work, instrumentation and observations.

Astronomy is also very interdisciplinary — using maths, chemistry and physics, and astronomers have often been and continue to be at the forefront of computing.

Q: As Director General of ESO, what was your most memorable moment or proudest achievement?

A. I cannot not mention here the first lights of two of the Very Large Telescope’s (VLT) four unit telescopes, Melipal and Yepun, those were magical moments.

|

One of the big adventures that I had as Director General was with ALMA.

|

One of the big adventures that I had as Director General was with ALMA. A memorable moment was going to Washington to sign the ALMA agreement with the National Science Foundation in the US on the 24th February 2003, which also happened to be my 60th birthday. The ALMA groundbreaking in November of that year was a beautiful ceremony.

Of course, I was proud of the many big discoveries using ESO’s VLT, including the first image of an exoplanet and work on stars close to the galactic centre, which led to last year’s Nobel Prize for research on the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole. I enjoyed them all tremendously.

I am also proud of my work putting things in place for an extremely large telescope. I involved the community from the start, and I moved very quickly to create five working groups, to start preparing what the ELT would be. At the end of 2006, we had a meeting in Marseille where two possible designs were shown to meet the mark. Eventually, the novel 5 mirror design, invented by ESO engineers, was chosen. I was very happy that my final year as Director General in 2006–2007 was so fruitful. My whole time at ESO was very exciting.

Q: Do you think that the public perspective of women in science has changed over the course of your career?

A. I think it has changed a lot, and the simple reason is because there are many more women in science. Recently, it has become a big topic and I hope that gender inequalities will disappear in the near future.

When I was a postdoc, I was one of two female postdocs on campus. I was pregnant at the time and you can imagine how people looked at me. It was difficult to be treated normally: some people treated you too well and others not well at all.

However, I didn’t suffer very much from lack of role models, because I didn’t pay much attention to the fact I was a woman. I compared myself to men all the time without any worry or second thoughts. But of course, there weren’t many women to compare myself to.

Q: What have you found most rewarding about your career?

A. All along, I have very much enjoyed the beauty and immense progress of astrophysics. It really makes my life interesting and fulfilling. Not just what I do, but all the work of the astrophysics community. The things we understand and discover as astrophysicists make me very interested and happy.

Earlier in my career, I enjoyed tremendously being in my corner, solving equations and coming up with new ideas. Part of me regrets that I somehow got out of that. But of course, other opportunities came and I have very much enjoyed working with scientists, engineers and technicians to bring about promising facilities, especially when the scientific results started coming.

I enjoy being an astrophysicist together with astrophysicists all over the world — it's like an extended family. And there’s never a dull moment in astronomy!

Q: What are the upcoming scientific advances that you're excited about?

A. Of course, I am very excited about SKA. I have all kinds of interests in what SKA can do, including in magnetic fields, which I was very interested in earlier in my career as a theorist, galaxy evolution, which I worked on later, and gravitational waves.

I chaired the committee that selected the themes of the largest missions for ESA, so of course I am interested in these projects as well. We selected what became ATHENA, the Advanced Telescope for High-Energy Astrophysics, planning to launch in 2031, and LISA, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, planned for launch in 2034. I am also looking forward to the JWST.

I am interested in ESO’s VLT Interferometer. Having signed the contract for the GRAVITY instrument, I am excited by what its upgrade GRAVITY+ can do, for instance for exoplanets.

I am fascinated by everything to do with exoplanets. I have never worked on exoplanets myself but I follow the field closely, including results coming from the HARPS instrument on the ESO 3.6-metre telescope as well as SPHERE and ESPRESSO on the VLT. I am looking forward to finding proof of life somewhere else — I don’t think we’re too far from that.

Dark matter and dark energy are also topics I am very interested in. For dark matter, I hope we will get a lot more information from upcoming missions, including where it is and how it is distributed. I think dark energy is much more elusive and to solve this we need not only the ESA mission EUCLID, due to launch next year, but also another genius like Einstein.

Q: What challenges do you see for the next generation of scientists?

A. I think they will be different to the ones I have experienced. The golden age of astronomy extends further and further and this isn’t true for many disciplines. For astronomers, the realm of discovery is absolutely huge: natural treasures are plentiful and mysterious.

Everything has changed in the way research is done. I am sure that young people will know much better than I how to deal with these new methods. We saw the arrival of computers and the internet, they have high performance computers, machine learning, artificial intelligence, and whatever may come in the future. I trust young people to find their way in professions, like astronomy, that change all the time.

Q: What would you say has inspired you most throughout your career?

A. Different things have inspired me at different times. When I was younger, being alone in my room — just me and my subject — inspired me a lot.

Later on, I was inspired by the dream of what the instruments I got involved with were going to be able to do, as well as the day-to-day exchange with the people building them, and later seeing the results. The combination of all of these is what I still love today.

Numbers in this article

| 5 | Number of mirrors in the ELT’s novel design. |

| 8 | How many years Catherine was ESO Director General for. |

| 1971 | The year Catherine completed her PhD. |

| 2003 | The year that Catherine signed the agreement to build ALMA with the National Science Foundation in the US. |

| 2006 | The year the ELT’s five mirror design was chosen. |

Biography Catherine Cesarsky

Born in France, Catherine Cesarsky received a degree in Physical Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires and graduated with a PhD in Astronomy in 1971 from Harvard University. She worked at the California Institute of Technology, before moving to France in 1974 to become a staff member of the Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique (CEA). She became the head of astrophysics in 1985, and director of all CEA basic research in physics and chemistry in 1994, leading a team of about 3000 scientists, engineers and technicians across a broad spectrum of science research programmes. She then joined ESO as Director General between 1999 and 2007, where she oversaw the signing of agreements to build ALMA and launched plans to build the ELT. From 2006 to 2009, Catherine Cesarsky was President of the International Astronomical Union, before becoming High Commissioner for CEA, advising the French government on science and energy issues between 2009 and 2012, then a high level science advisor there.

Catherine Cesarsky’s research activities span several areas of astrophysics. The first part of her career was devoted to the high-energy domain, including studying the propagation and composition of galactic cosmic rays. She then turned to infrared astronomy, becoming Principal Investigator of the ISOCAM camera onboard the European Space Agency’s Infrared Space Observatory, which flew between 1995 and 1998. ISOCAM studied the infrared emission from a variety of galactic and extragalactic sources and yielded new and exciting results on star formation and galactic evolution.

She is Grand Officier de l’Ordre National du Mérite and Grand Officier de l’Ordre de la Légion d’Honneur, levels attained by few people in France.