Press Release

Dramatic Eruption on Comet Halley Surprises Astronomers

A most unexpected observation

22 February 1991

It was early in the morning of Tuesday, February 12, and ESO astronomers Olivier Hainaut and Alain Smette [1] did not know what to believe. Observing with the Danish 1.54-metre telescope at the La Silla observatory, they had just finished a one-hour exposure of a small sky field in the constellation of Hydra (the Water Snake). This work was part of the ESO monitoring programme of famous Comet Halley and the astronomers felt that something was quite wrong.

When this comet passed near the Sun in early 1986, it was a bright, naked-eye object with a spectacular tail. Now, 5 years later, it has moved more than 2140 million kilometres away from the Sun and the sunlight reflected from the 15-kilometre "dirty snowball" nucleus has become so faint that it can hardly be seen, even with large, modern telescopes.

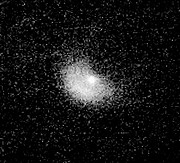

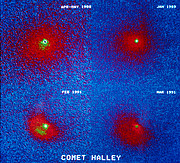

The astronomers were surprised because instead of the faint, tiny spot of light which was all the same telescope could see of Halley in 1990 [2], there was now a rather bright and extended "nebula" in the middle of the picture on the computer screen. In fact, this object was almost 300 times brighter than the image of Halley's nucleus was predicted to be.

Could it perhaps be another celestial body, a nebula in the Milky Way or even another comet which happened to be seen in exactly the same direction as Comet Halley? Or maybe it was just a reflection from a bright star in the telescope optics?

But a second, shorter exposure confirmed that this nebula was not an artifact and additional images obtained during the following nights showed that this nebula moved in the same direction and with exactly the same speed as Comet Halley. There was no longer any doubt: it is indeed Halley which has undergone a tremendous outburst!

This observation has caused a certain upheaval among cometary scientists, because no cornet has ever been found to have an outburst this far from the Sun. Nor is such an event predicted by any current theory. So whatever happened to Comet Halley?

What does a cometary nucleus look like?

Close-up observations of Comet Halley's nucleus by several spacecraft took place in March 1986, in particular by the European Space Agency's Giotto, and it is now known that a cometary nucleus mainly consists of water ice, mixed with dust grains of different sizes. Some of these grains are mineral, but chemical analysis by Giotto's instruments clearly showed that many of them are carbon-rich and therefore contain organic compounds. The amazingly dark surface of Halley's nucleus (it reflects only 4% of the infalling sunlight) most probably harbours a lot of organic material in the form of a thin crust of dust grains. The structure of Halley's nucleus has sometimes been likened with a chocolate¬covered ice cream of avocado-shape, albeit 15 kilometres long and 6 kilometres across. Another frequently used picture is that of a dirty snowdrift in spring-time, slowly melting at the wayside.

As the orbital motion of a cornet brings it nearer to the Sun, the dark surface on its nucleus increasingly absorbs the Sun's rays and the temperature steadily rises. The ices on the surface and below the crust begin to sublimate and a cloud of gas is formed around the nucleus; at the same time dust grains begin to fall out. A dense cloud (the "coma") soon shrouds the nucleus. Shortly thereafter one or more tails are formed when the gas molecules are pushed outwards by the fast particles in the solar wind and the dust grains are lost behind as the cornet moves on in its orbit.

Close to the Sun, a cornet's brightness may change from time to time, due to the sudden, explosive release of large quantities of gas and dust from the nucleus. Such outbursts take place from big vents on the surface, in the form of fast-flowing jets of dust and gas. But this activity gradually ceases, as the comet moves away from the Sun and the temperature of the surface decreases. After a while, everything freezes, no more gas and dust is lost and the remaining material in the surrounding cloud soon disperses into space, leaving the "naked" nucleus behind.

How can Halley's recent outburst be explained?

Until the present event, Comet Halley behaved exactly as described above.

Already in 1988, there was only a thin cloud left around the nucleus, in 1989 the cloud was still there, but even fainter, and in 1990, only the nucleus could be seen. And so, Halley was declared asleep and few astronomers, if any, believed that anything different from a tiny light point would be observed before the time of its next return in the year 206l.

Because of their extreme faintness, it has so far been possible to observe only two other comets at more than 2000 million kilometres from the Sun [3], and Halley is the only comet which has ever been observed to have an outburst at this large distance. Moreover, a preliminary analysis of the structure of the cloud around the nucleus (see the photo which accompanies this Press Release) indicates that the current outburst must have lasted a certain time. Since there is no obvious difference between the images obtained over a 5-day period, the surrounding cloud must be continuously replenished with new material from the nucleus. We see the comet and its surrounding cloud "from behind", as it moves away from us, towards the outer reaches of the solar system.

At the time of the observation, Halley was about midway between the planets Saturn and Uranus. At this large distance, the sunlight is very faint and the temperature on the surface of the nucleus is only around -200°C, so cold that the snow, ice and dust must be frozen solid. It is therefore not a simple matter to explain the outburst of Halley.

There appear to be three possibilities: 1) a collision with another small, unknown body, 2) the release of a large amount of energy, stored in some way in the interior of the nucleus, or 3) the interaction with highly energetic particles in the solar wind.

Concerning the first possibility, very little is known about the population of small bodies in the outer solar system. There may be more than now thought, but the chance of hitting the relatively small nucleus of Halley seems extremely remote. Moreover, it is not clear how such a catastrophic event could lead to the apparently steady outflow, observed at this moment.

In a similar way, virtually nothing is known with certainty about the inner structure of cometary nuclei. About half a dozen theories have been proposed about the chemical and physical properties of the ice-dust mixture, but none of them can easily explain how large quantities of heat or mechanical energy can be stored during the approach to the Sun and then released after such a long time.

And thirdly, even though the Sun is presently in a phase of maximal activity and emits large amounts of energetic particles at frequent intervals, it is very doubtful whether they would carry enough energy to heat the surface of Halley's nucleus to produce the observed, spectacular effect at this large distance from the Sun.

Observations of Halley will be intensified

Two things are clear, however. Astrophysicists with special interest in comets will now have to rethink their theoretical models of cometary nuclei. And Halley has once again shown that it deserves to be the most famous comet of them all.

An intensified Halley observing schedule is being implemented at ESO and the comet is now monitored as often as other telescope commitments allow. Photometric observations by ESO astronomer Edmond Giraud with the ESO/MPI 2.2-metre telescope have shown that the colour of Halley's coma is very similar to that of the Sun. This strongly indicates that the cloud mostly, if not exclusively, consists of dust grains that reflect the sunlight. This was confirmed by Alain Smette, who obtained a spectrum of Halley with the 3.5-metre New Technology Telescope (NTT) in the early morning of February 22; a first inspection did not show any emission lines which could be attributed to gas in the coma. This NTT observation constitutes an absolute record in cometary astronomy: never before has a spectrum been successfully obtained of a comet at such a large distance from the Sun.

ESO has officially announced the discovery of Halley's surprising outburst in Circular 5189 of the International Astronomical Union and other observatories will soon join in the watch.

Notes

[1] Both astronomers are on long-term assignment to ESO from institut d'Astrophysique, Liege, Belgium

[2] See eso9002, or ESO Messenger 61, page 18 (September 1990)

[3] Comets Cernis (1983 XII) and Bowell (1982 I), both of which are "new" comets and therefore, contrary to Comet Halley, move in open orbits and will not again visit the inner solar system.

Contacts

Richard West

ESO EPR Dept

Garching, Germany

Email: information@eso.org

About the Release

| Release No.: | eso9103 |

| Legacy ID: | PR 03/91 |

| Name: | Comet Halley |

| Type: | Solar System : Interplanetary Body : Comet |

| Facility: | Danish 1.54-metre telescope |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.