- How astronomers design observations to test their ideas

- How staff at ESO’s observatories help them obtain their data

- How these data are transformed into the beautiful images you see online

When browsing through the captivating images of the cosmos that we routinely publish you may have asked yourself ‘how did they take this image?’ The answer is… complicated. In this blog post we’ll tell you how these pictures come to be and the role of everyone that makes them possible.

It all begins with an idea

Astronomers don’t just randomly point telescopes at the sky –– they always want to answer specific questions. How do stars form in galaxies? What’s the composition of the atmospheres of exoplanets? What’s the mass of the black hole at the centre of our galaxy? They then think about what observations are needed to answer those questions, and identify which observatories have the telescopes and instruments required to obtain that data.

Everyone wants to get a chance to observe their favourite astronomical targets, but the amount of observing time available at any given telescope is always limited. Astronomers therefore have to compete for observing time with their peers.

They do so by writing proposals where they detail their scientific problem and how they plan to tackle it. These proposals are evaluated by a panel of experts based on different criteria: how scientifically relevant is the question the team wants to answer? Can their proposed observations actually address this question? Are they using the right telescope and instrument for the job?

Organising all this requires a considerable amount of work. At ESO this is led by the so-called Observing Programme Office but many other people are involved. For instance, ESO astronomers at the User Support Department help their peers with any questions they may have while preparing their proposals.

From idea to reality

The lucky few whose proposals get accepted need to prepare the observations. You can think of them as recipes with a sequence of steps: point the telescope to the target, configure the instrument in the desired way, gather data for some time… Astronomical instruments are highly sophisticated and it can take years of experience to master them. To make it as easy as possible for everyone to use them, ESO provides a dedicated online tool that simplifies the process. Users only need to specify the sequence of steps, and trained ESO staff will execute them at the telescope. It’s like having professional chefs cooking your favourite recipes on demand! The User Support Department once again assists astronomers when preparing their observations.

Most of the time astronomers don’t even have to travel to the observatories. Instead, their requested observations are stored in a database, and ESO staff on site will decide on the fly what to observe at any given time. This depends on multiple factors, like the scientific priority of the observations, how urgent they are, or the ambient conditions –– not all projects require perfect weather or a moonless sky, for instance.[1]

This way of observing is called “service mode”, and it allows astronomers to optimise precious observing time, allocating the best conditions to those projects that most need them. But some observing programmes can be particularly tricky, or may require the astronomers who proposed it to make decisions in real time. In this case, the users can visit the observatory, or join in remotely through video conference, to guide the ESO staff on site during the observations.

Once observations are over, the data are automatically transferred to an online archive –– more on that later. But the job isn’t complete yet. What if something went wrong during the observations, compromising the quality of the data? Perhaps the atmospheric turbulence increased, blurring the images too much? Or maybe some clouds passed by? The staff on site carefully verifies that the data meet the requirements requested by the users, and if needed they can flag those observations to be repeated later on.

With so many telescopes and instruments at ESO’s observatories, technical problems can and do happen, and the night staff must be ready to troubleshoot them quickly, to avoid wasting telescope time. This often requires calling engineers in the middle of the night! Engineers at our observatories cover many areas of expertise: optics, mechanics, electronics, software, instrumentation… Together they make sure that all systems perform as expected. They might not be the ones who “press the shutter”, to use a photographic analogy, but without them astronomers wouldn’t get their data, and you would not enjoy such magnificent views of the cosmos or get answers to the most pressing questions about our Universe.

A new day begins

Paraphrasing Frank Sinatra: “I want to wake up in an observatory that never sleeps.” You might think that there’s not much activity at an observatory during the day, but that’s not quite true. When the night is over, the night crew goes to sleep and the day crew takes over. They review problems that happened during the night, fix pending issues, carry out preemptive maintenance tasks, and plan ahead for the upcoming days. Visitors to our sites are often surprised by how hectic the control room can be during the day. But it is precisely thanks to the hard work of the day crew that all systems are ready to go when the Sun sets.

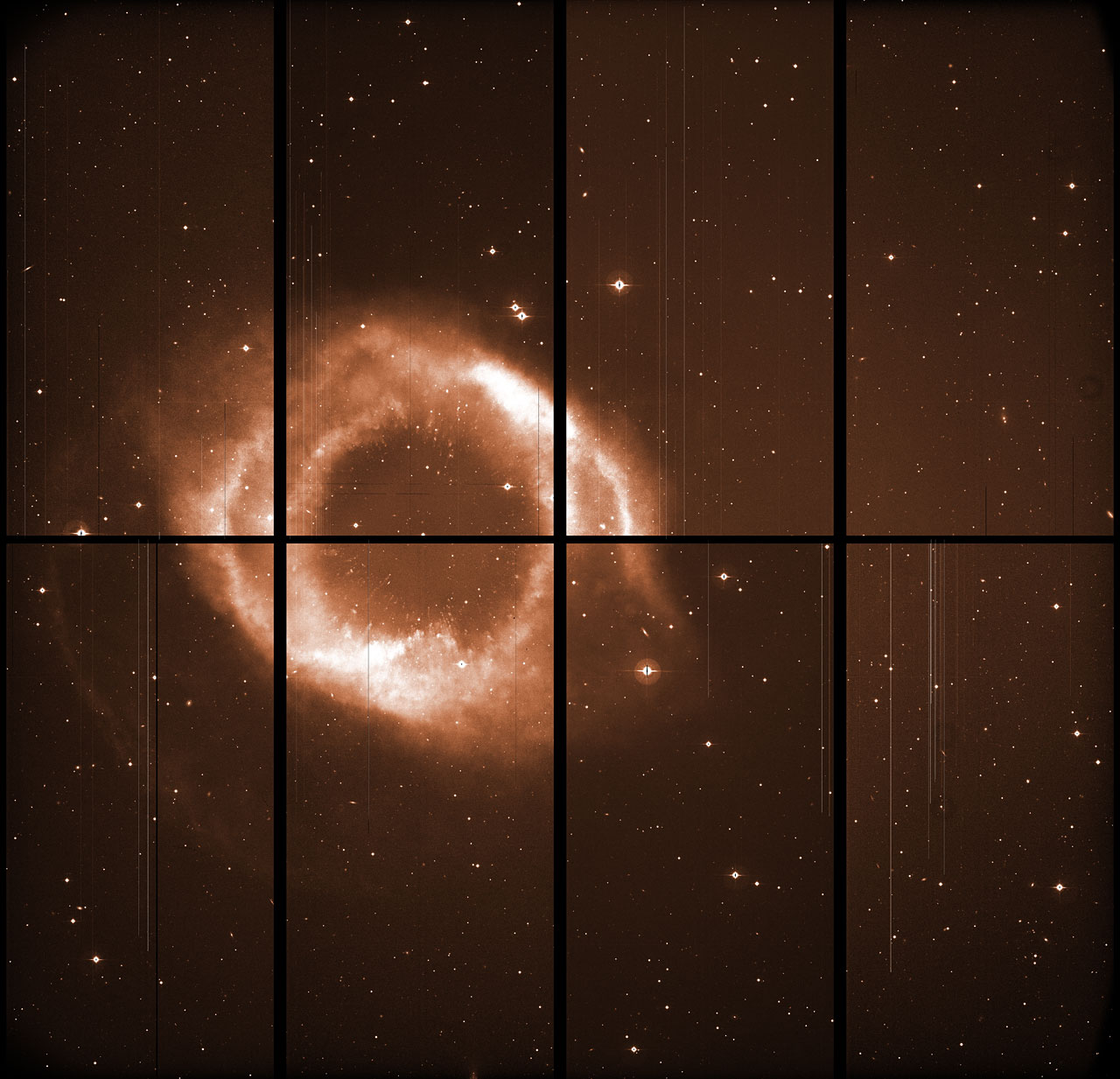

Not even the instruments rest during the day, because they spend quite a few hours automatically taking calibration data. Why? Raw data straight out of the instruments can’t generally be used for scientific purposes. Look at the image below, for instance, which shows the Helix Nebula observed with the Wide Field Imager instrument at ESO’s La Silla Observatory. You can see some cosmetic artefacts like bright and dark columns caused by dead pixels. Also, the level of illumination can vary across the image, among other effects. Calibration data are thus needed to measure and remove these features before astronomers can use these images for scientific purposes. Other instruments like spectrographs, which decompose light into its constituent colours, require a different set of calibrations.

The day crew also uses calibration data to monitor the health of the instruments. Just like a doctor can tell if something is wrong by looking at an X-ray plate or reading the results of a blood test, astronomers and engineers inspect calibrations daily, both visually and through numeric analysis, to check that instruments are performing as expected.

Cooking the raw data

Somewhere thousands of kilometres away from the observatory, an astronomer wakes up to one of the best emails they could get in the morning: an automatic notification that some of their targets were observed the night before. Eager to see what the telescope saw, they immediately proceed to download the observations from the ESO science archive and “reduce” them.

No, this doesn’t mean that they shrink the data! “Data reduction” is how astronomers refer to the process of transforming the raw data and calibrations captured by the instrument into science-ready data. To do so they use software tools called data reduction pipelines. ESO’s Pipeline Systems Group maintains a set of pipelines tailored to each specific instrument, which anyone can freely download. These pipelines are also regularly tested by ESO astronomers, implementing new features and fixing bugs. This is quite a lot of work, but these public pipelines save time for users, and they also ensure that the scientific results obtained from ESO data can be independently verified by others.

Once astronomers have fully processed and analysed their data, they write up their findings in the form of scientific papers and publish them in specialised journals, where they will be reviewed by other colleagues.

Spreading the word

Besides sharing their results with their peers, astronomers often pitch them to ESO’s Department of Communication, which evaluates them and may end up publicising them among journalists and the general public via press releases, pictures of the week, ESOcasts or blog posts.

This is done by a team of science writers, astronomers, web developers and visual artists. In particular, the latter are the ones who transform the data captured by the instruments into the final images you see. Unlike a commercial camera like the one in your smartphone, which captures images in colour, astronomical instruments register images in greyscale, measuring only the intensity of light at each pixel. One can insert special filters that only let through light of certain colours or wavelengths, which allow astronomers to probe the distribution of, say, various chemical elements, or different types of stars.

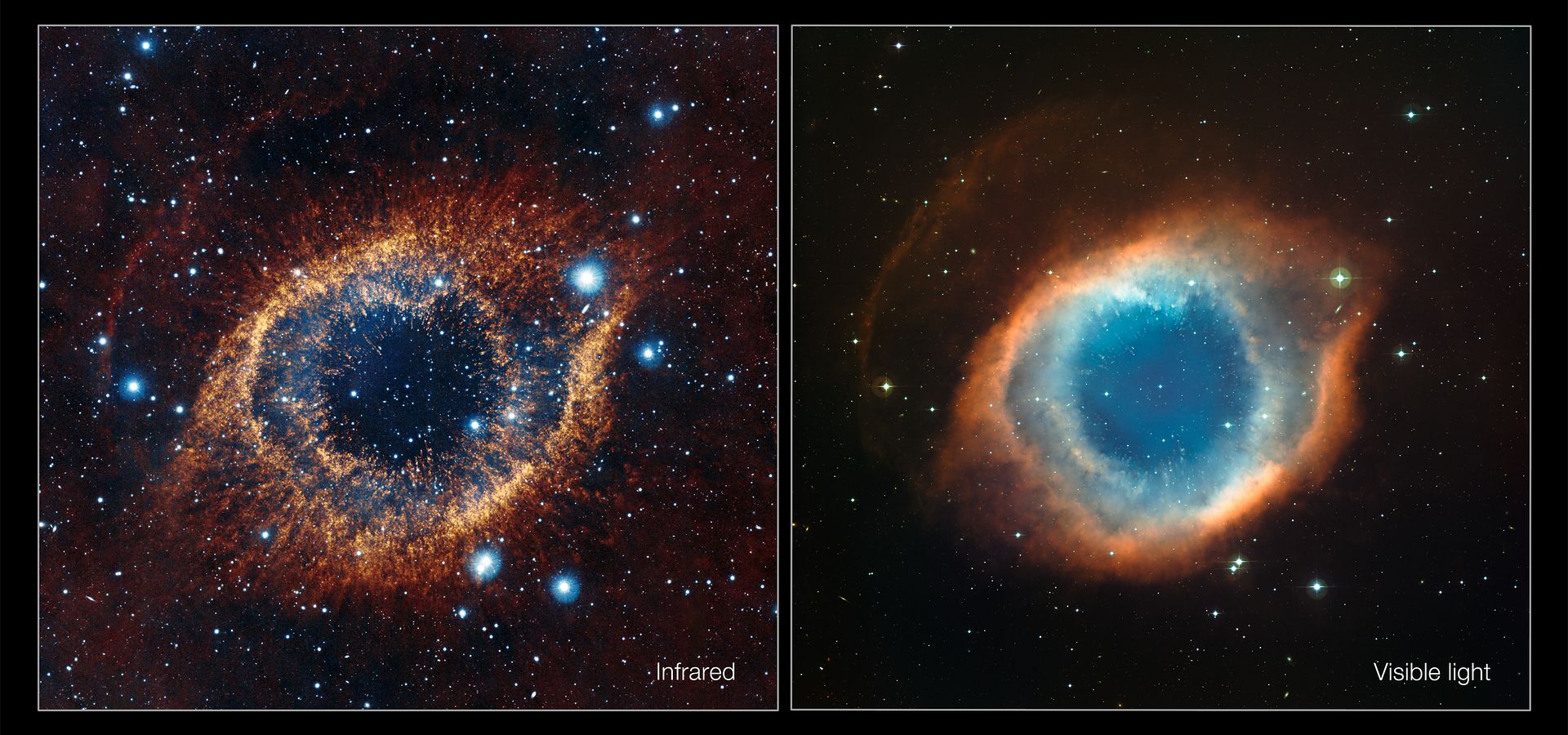

This is more efficient than having tiny red, green and blue filters pre-built on the detector itself, like your smartphone does, but it means that images taken separately through different filters need to be combined a posteriori into a coloured image. The right hand image below shows again the Helix Nebula that we saw earlier, where observations through red, green and blue filters have been combined together.

We don’t have to restrict ourselves to the colours that we humans can see. The image to the left below shows the same nebula observed at infrared wavelengths with the VISTA telescope at ESO’s Paranal Observatory. In this case different infrared filters have been displayed as red, green and blue; while we wouldn’t be able to see this with our eyes, such a colour combination reveals new and intricate details that don’t show up in the visible-light image.

Wrapping up

As you can see, there is never a single person solely responsible for the images we share with you: they are always the result of the coordinated work of many people with different professional backgrounds. And in this article we haven’t even mentioned those responsible for developing and building our telescopes and instruments –– both in-house at ESO and at other institutions and companies ––, or the logistics personnel that take care of our staff at the observatories in the middle of the Atacama Desert, or the administrative staff who keep everything running…

So, next time you see a beautiful image of a distant galaxy, a star-forming nebula or a new exoplanet, remember that there are hundreds of people behind it, working hard to share the excitement of the universe with you!

Notes

[1] One example is ESO’s own Cosmic Gems programme, which makes use of bad weather conditions to capture spectacular images for outreach purposes.

Links

- A day in the life of an ALMA and a Paranal astronomer

- What does a telescope operator do?

- Paranal through the eyes of a mechanical engineer

Biography Juan Carlos Muñoz Mateos

Juan Carlos Muñoz Mateos is Media Officer at ESO in Garching and editor of the ESO blog. He completed his PhD in astrophysics at Complutense University in Madrid (Spain). Previously he worked for several years at ESO in Chile, combining his research on galaxy evolution with duties at Paranal Observatory.