Press Release

Oldest Solar Twin Identified

ESO’s VLT provides new clues to help solve lithium mystery

28 August 2013

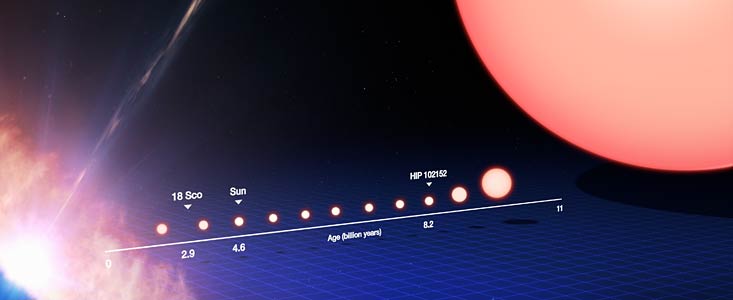

An international team led by astronomers in Brazil has used ESO’s Very Large Telescope to identify and study the oldest solar twin known to date. Located 250 light-years from Earth, the star HIP 102152 is more like the Sun than any other solar twin — except that it is nearly four billion years older. This older, but almost identical, twin gives us an unprecedented chance to see how the Sun will look when it ages. The new observations also provide an important first clear link between a star’s age and its lithium content, and in addition suggest that HIP 102152 may be host to rocky terrestrial planets.

Astronomers have only been observing the Sun with telescopes for 400 years — a tiny fraction of the Sun’s age of 4.6 billion years. It is very hard to study the history and future evolution of our star, but we can do this by hunting for rare stars that are almost exactly like our own, but at different stages of their lives. Now astronomers have identified a star that is essentially an identical twin to our Sun, but 4 billion years older — almost like seeing a real version of the twin paradox in action [1].

Jorge Melendez (Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil), the leader of the team and co-author of the new paper explains: “For decades, astronomers have been searching for solar twins in order to know our own life-giving Sun better. But very few have been found since the first one was discovered in 1997. We have now obtained superb-quality spectra from the VLT and can scrutinise solar twins with extreme precision, to answer the question of whether the Sun is special.”

The team studied two solar twins [2] — one that was thought to be younger than the Sun (18 Scorpii) and one that was expected to be older (HIP 102152). They used the UVES spectrograph on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at ESO's Paranal Observatory to split up the light into its component colours so that the chemical composition and other properties of these stars could be studied in great detail.

They found that HIP 102152 in the constellation of Capricornus (The Sea Goat) is the oldest solar twin known to date. It is estimated to be 8.2 billion years old, compared to 4.6 billion years for our own Sun. On the other hand 18 Scorpii was confirmed to be younger than the Sun — about 2.9 billion years old.

Studying the ancient solar twin HIP 102152 allows scientists to predict what may happen to our own Sun when it reaches that age, and they have already made one significant discovery. “One issue we wanted to address is whether or not the Sun is typical in composition,” says Melendez. “Most importantly, why does it have such a strangely low lithium content?”

Lithium, the third element in the periodic table, was created in the Big Bang along with hydrogen and helium. Astronomers have pondered for years over why some stars appear to have less lithium than others. With the new observations of HIP 102152, astronomers have taken a big step towards solving this mystery by pinning down a strong correlation between a Sun-like star’s age and its lithium content.

Our own Sun now has just 1% of the lithium content that was present in the material from which it formed. Examinations of younger solar twins have hinted that these younger siblings contain significantly larger amounts of lithium, but up to now scientists could not prove a clear correlation between age and lithium content [3].

TalaWanda Monroe (Universidade de São Paulo), the lead author on the new paper, concludes: “We have found that HIP 102152 has very low levels of lithium. This demonstrates clearly for the first time that older solar twins do indeed have less lithium than our own Sun or younger solar twins. We can now be certain that stars somehow destroy their lithium as they age, and that the Sun's lithium content appears to be normal for its age.” [4]

A final twist in the story is that HIP 102152 has an unusual chemical composition pattern that is subtly different to most other solar twins, but similar to the Sun. They both show a deficiency of the elements that are abundant in meteorites and on Earth. This is a strong hint that HIP 102152 may host terrestrial rocky planets [5].

Notes

[1] Many people have heard of the twin paradox: one identical twin takes a space journey and comes back to Earth younger than their sibling. Although there is no time travelling involved here, we see two distinctly different ages for these two very similar stars — snapshots of the Sun’s life at different stages.

[2] Solar twins, solar analogues and solar-type stars are categories of stars according to their similarity to our own Sun. Solar twins are the most similar to our Sun, as they have very similar masses, temperatures, and chemical abundances. Solar twins are rare but the other classes, where the similarity is less precise, are much more common.

[3] Previous studies have indicated that a star’s lithium content could also be affected if it hosts giant planets (eso0942, eso0118, Nature paper), although these results have been debated (ann1046).

[4] It is still unclear exactly how lithium is destroyed within the stars, although several processes have been proposed to transport lithium from the surface of a star into its deeper layers, where it is then destroyed.

[5] If a star contains less of the elements that we commonly find in rocky bodies, this indicates that it is likely to host rocky terrestrial planets because such planets lock up these elements as they form from a large disc surrounding the star. The suggestion that HIP 102152 may host such planets is further reinforced by the radial velocity monitoring of this star with ESO's HARPS spectrograph, which indicates that inside the star’s habitable zone there are no giant planets. This would allow the existence of potential Earth-like planets around HIP 102152; in systems with giant planets existing close in to their star, the chances of finding terrestrial planets are much less as these small rocky bodies are disturbed and disrupted.

More information

This research was presented in a paper to appear in “High precision abundances of the old solar twin HIP 102152: insights on Li depletion from the oldest Sun”, by TalaWanda Monroe et al. in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The team is composed of TalaWanda R. Monroe, Jorge Meléndez (Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil [USP]), Iván Ramírez (The University of Texas at Austin, USA), David Yong (Australian National University, Australia [ANU]), Maria Bergemann (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Germany), Martin Asplund (ANU), Jacob Bean, Megan Bedell (University of Chicago, USA), Marcelo Tucci Maia (USP), Karin Lind (University of Cambridge, UK), Alan Alves-Brito, Luca Casagrande (ANU), Matthieu Castro, José-Dias do Nascimento (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil), Michael Bazot (Centro de Astrofísica da Universidade de Porto, Portugal) and Fabrício C. Freitas (USP).

ESO is the foremost intergovernmental astronomy organisation in Europe and the world’s most productive ground-based astronomical observatory by far. It is supported by 15 countries: Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Czechia, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. ESO carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities enabling astronomers to make important scientific discoveries. ESO also plays a leading role in promoting and organising cooperation in astronomical research. ESO operates three unique world-class observing sites in Chile: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. At Paranal, ESO operates the Very Large Telescope, the world’s most advanced visible-light astronomical observatory and two survey telescopes. VISTA works in the infrared and is the world’s largest survey telescope and the VLT Survey Telescope is the largest telescope designed to exclusively survey the skies in visible light. ESO is the European partner of a revolutionary astronomical telescope ALMA, the largest astronomical project in existence. ESO is currently planning the 39-metre European Extremely Large optical/near-infrared Telescope, the E-ELT, which will become “the world’s biggest eye on the sky”.

Links

- Research paper

- FAQ about ESO and Brazil

- Photos of the VLT

Contacts

TalaWanda R. Monroe

Universidade de São Paulo

São Paulo, Brazil

Tel: +55 11 3091 2815

Email: tmonroe@usp.br

Jorge Meléndez

Universidade de São Paulo

São Paulo, Brazil

Tel: +55 11 3091 2840

Email: jorge.melendez@iag.usp.br

Richard Hook

ESO, Public Information Officer

Garching bei München, Germany

Tel: +49 89 3200 6655

Cell: +49 151 1537 3591

Email: rhook@eso.org

About the Release

| Release No.: | eso1337 |

| Name: | HIP 102152 |

| Type: | Milky Way : Star |

| Facility: | Very Large Telescope |

| Science data: | 2013ApJ...774L..32M |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.