Press Release

The Wild Early Lives of Today's Most Massive Galaxies

Dramatic star formation cut short by black holes

25 January 2012

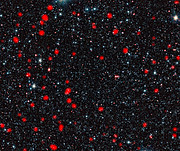

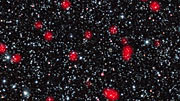

Using the APEX telescope, a team of astronomers has found the strongest link so far between the most powerful bursts of star formation in the early Universe, and the most massive galaxies found today. The galaxies, flowering with dramatic starbursts in the early Universe, saw the birth of new stars abruptly cut short, leaving them as massive — but passive — galaxies of aging stars in the present day. The astronomers also have a likely culprit for the sudden end to the starbursts: the emergence of supermassive black holes.

Astronomers have combined observations from the LABOCA camera on the ESO-operated 12-metre Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) telescope [1] with measurements made with ESO’s Very Large Telescope, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, and others, to look at the way that bright, distant galaxies are gathered together in groups or clusters.

The more closely the galaxies are clustered, the more massive are their halos of dark matter — the invisible material that makes up the vast majority of a galaxy’s mass. The new results are the most accurate clustering measurements ever made for this type of galaxy.

The galaxies are so distant that their light has taken around ten billion years to reach us, so we see them as they were about ten billion years ago [2]. In these snapshots from the early Universe, the galaxies are undergoing the most intense type of star formation activity known, called a starburst.

By measuring the masses of the dark matter halos around the galaxies, and using computer simulations to study how these halos grow over time, the astronomers found that these distant starburst galaxies from the early cosmos eventually become giant elliptical galaxies — the most massive galaxies in today’s Universe.

“This is the first time that we've been able to show this clear link between the most energetic starbursting galaxies in the early Universe, and the most massive galaxies in the present day," explains Ryan Hickox (Dartmouth College, USA and Durham University, UK), the lead scientist of the team.

Furthermore, the new observations indicate that the bright starbursts in these distant galaxies last for a mere 100 million years — a very short time in cosmological terms — yet in this brief time they are able to double the quantity of stars in the galaxies. The sudden end to this rapid growth is another episode in the history of galaxies that astronomers do not yet fully understand.

“We know that massive elliptical galaxies stopped producing stars rather suddenly a long time ago, and are now passive. And scientists are wondering what could possibly be powerful enough to shut down an entire galaxy’s starburst,” says Julie Wardlow (University of California at Irvine, USA and Durham University, UK), a member of the team.

The team’s results provide a possible explanation: at that stage in the history of the cosmos, the starburst galaxies are clustered in a very similar way to quasars, indicating that they are found in the same dark matter halos. Quasars are among the most energetic objects in the Universe — galactic beacons that emit intense radiation, powered by a supermassive black hole at their centre.

There is mounting evidence to suggest the intense starburst also powers the quasar by feeding enormous quantities of material into the black hole. The quasar in turn emits powerful bursts of energy that are believed to blow away the galaxy’s remaining gas — the raw material for new stars — and this effectively shuts down the star formation phase.

“In short, the galaxies’ glory days of intense star formation also doom them by feeding the giant black hole at their centre, which then rapidly blows away or destroys the star-forming clouds,” explains David Alexander (Durham University, UK), a member of the team.

Notes

[1] The 12-metre-diameter APEX telescope is located on the Chajnantor plateau in the foothills of the Chilean Andes. APEX is a pathfinder for ALMA, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, a revolutionary new telescope that ESO, together with its international partners, is building and operating, also on the Chajnantor plateau. APEX is itself based on a single prototype antenna constructed for the ALMA project. The two telescopes are complementary: for example, APEX can find many targets across wide areas of sky, which ALMA will be able to study in great detail. APEX is a collaboration between the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR), the Onsala Space Observatory (OSO) and ESO.

[2] These distant galaxies are known as submillimetre galaxies. They are very bright galaxies in the distant Universe in which intense star formation occurs. Because of this extreme distance, their infrared light from dust grains heated by starlight is redshifted into longer wavelengths, and the dusty galaxies are therefore best observed in submillimetre wavelengths of light.

More information

This research is presented in a paper to appear in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society on 26 January 2012.

The team is composed of Ryan C. Hickox (Dartmouth College, Hanover, USA; Department of Physics, Durham University (DU); STFC Postdoctoral Fellow, UK), J. L. Wardlow (Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of California at Irvine, USA; Department of Physics, DU, UK), Ian Smail (Institute for Computational Cosmology, DU, UK), A. D. Myers (Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Wyoming, USA), D. M. Alexander (Department of Physics, DU, UK), A. M. Swinbank (Institute for Computational Cosmology, DU, UK), A. L. R. Danielson (Institute for Computational Cosmology, DU, UK), J. P. Stott (Department of Physics, DU, UK), S. C. Chapman (Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK), K. E. K. Coppin (Department of Physics, McGill University, Canada), J. S. Dunlop (Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, UK), E. Gawiser (Department of Physics and Astronomy, The State University of New Jersey, USA), D. Lutz (Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Germany), P. van der Werf (Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, The Netherlands), A. Weiß (Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Germany).

The year 2012 marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of the European Southern Observatory (ESO). ESO is the foremost intergovernmental astronomy organisation in Europe and the world’s most productive astronomical observatory. It is supported by 15 countries: Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Czechia, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. ESO carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities enabling astronomers to make important scientific discoveries. ESO also plays a leading role in promoting and organising cooperation in astronomical research. ESO operates three unique world-class observing sites in Chile: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. At Paranal, ESO operates the Very Large Telescope, the world’s most advanced visible-light astronomical observatory and two survey telescopes. VISTA works in the infrared and is the world’s largest survey telescope and the VLT Survey Telescope is the largest telescope designed to exclusively survey the skies in visible light. ESO is the European partner of a revolutionary astronomical telescope ALMA, the largest astronomical project in existence. ESO is currently planning a 40-metre-class European Extremely Large optical/near-infrared Telescope, the E-ELT, which will become “the world’s biggest eye on the sky”.

ALMA, an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of Europe, North America and East Asia in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA construction and operations are led on behalf of Europe by ESO, on behalf of North America by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), and on behalf of East Asia by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ). The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.

Links

Contacts

Ryan Hickox

Dartmouth College

Hanover, New Hampshire, USA

Tel: +1 603 646 2962

Email: ryan.c.hickox@dartmouth.edu

Douglas Pierce-Price

ESO ALMA/APEX Public Information Officer

Garching, Germany

Tel: +49 89 3200 6759

Email: dpiercep@eso.org

About the Release

| Release No.: | eso1206 |

| Name: | Galaxies |

| Type: | Early Universe : Cosmology : Morphology : Deep Field |

| Facility: | Atacama Pathfinder Experiment, MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope, Spitzer Space Telescope, Very Large Telescope |

| Instruments: | FORS2, HAWK-I, ISAAC, LABOCA, VIMOS, WFI |

| Science data: | 2012MNRAS.421..284H |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.