Press Release

New Quasar Studies Keep Fundamental Physical Constant Constant

Very Large Telescope sets stringent limit on possible variation of the fine-structure constant over cosmological time.

31 March 2004

Detecting or constraining the possible time variations of fundamental physical constants is an important step toward a complete understanding of basic physics and hence the world in which we live. A step in which astrophysics proves most useful. Previous astronomical measurements of the fine structure constant - the dimensionless number that determines the strength of interactions between charged particles and electromagnetic fields - suggested that this particular constant is increasing very slightly with time. If confirmed, this would have very profound implications for our understanding of fundamental physics. New studies, conducted using the UVES spectrograph on Kueyen, one of the 8.2-m telescopes of ESO's Very Large Telescope array at Paranal (Chile), secured new data with unprecedented quality. These data, combined with a very careful analysis, have provided the strongest astronomical constraints to date on the possible variation of the fine structure constant. They show that, contrary to previous claims, no evidence exist for assuming a time variation of this fundamental constant.

A fine constant

To explain the Universe and to represent it mathematically, scientists rely on so-called fundamental constants or fixed numbers. The fundamental laws of physics, as we presently understand them, depend on about 25 such constants. Well-known examples are the gravitational constant, which defines the strength of the force acting between two bodies, such as the Earth and the Moon, and the speed of light.

One of these constants is the so-called "fine structure constant", alpha = 1/137.03599958, a combination of electrical charge of the electron, the Planck constant and the speed of light. The fine structure constant describes how electromagnetic forces hold atoms together and the way light interacts with atoms.

But are these fundamental physical constants really constant? Are those numbers always the same, everywhere in the Universe and at all times? This is not as naive a question as it may seem. Contemporary theories of fundamental interactions, such as the Grand Unification Theory or super-string theories that treat gravity and quantum mechanics in a consistent way, not only predict a dependence of fundamental physical constants with energy - particle physics experiments have shown the fine structure constant to grow to a value of about 1/128 at high collision energies - but allow for their cosmological time and space variations. A time dependence of the fundamental constants could also easily arise if, besides the three space dimensions, there exist more hidden dimensions.

Already in 1955, the Russian physicist Lev Landau considered the possibility of a time dependence of alpha. In the late 1960s, George Gamow in the United States suggested that the charge of the electron, and therefore also alpha, may vary. It is clear however that such changes, if any, cannot be large or they would already have been detected in comparatively simple experiments. Tracking these possible changes thus requires the most sophisticated and precise techniques.

Looking back in time

In fact, quite strong constraints are already known to exist for the possible variation of the fine structure constant alpha. One such constraint is of geological nature. It is based on measures taken in the ancient natural fission reactor located near Oklo (Gabon, West Africa) and which was active roughly 2,000 million years ago. By studying the distribution of a given set of elements - isotopes of the rare earths, for example of samarium - which were produced by the fission of uranium, one can estimate whether the physical process happened at a faster or slower pace than we would expect it nowadays. Thus we can measure a possible change of the value of the fundamental constant at play here, alpha. However, the observed distribution of the elements is consistent with calculations assuming that the value of alpha at that time was precisely the same as the value today. Over the 2 billion years, the change of alpha has therefore to be smaller than about 2 parts per 100 millions. If present at all, this is a rather small change indeed.

But what about changes much earlier in the history of the Universe?

To measure this we must find means to probe still further into the past. And this is where astronomy can help. Because, even though astronomers can't generally do experiments, the Universe itself is a huge atomic physics laboratory. By studying very remote objects, astronomers can look back over a long time span. In this way it becomes possible to test the values of the physical constants when the Universe had only 25% of is present age, that is, about 10,000 million years ago.

Very far beacons

To do so, astronomers rely on spectroscopy - the measurement of the properties of light emitted or absorbed by matter. When the light from a flame is observed through a prism, a rainbow is visible. When sprinkling salt on the flame, distinct yellow lines are superimposed on the usual colours of the rainbow, so-called emission lines. Putting a gas cell between the flame and the prism, one sees however dark lines onto the rainbow: these are absorption lines. The wavelength of these emission and absorption lines is directly related to the energy levels of the atoms in the salt or in the gas. Spectroscopy thus allows us to study atomic structure.

The fine structure of atoms can be observed spectroscopically as the splitting of certain energy levels in those atoms. So if alpha were to change over time, the emission and absorption spectra of these atoms would change as well. One way to look for any changes in the value of alpha over the history of the Universe is therefore to measure the spectra of distant quasars, and compare the wavelengths of certain spectral lines with present-day values.

Quasars are here only used as a beacon - the flame - in the very distant Universe. Interstellar clouds of gas in galaxies, located between the quasars and us on the same line of sight and at distances varying from six to eleven thousand of million light years, absorb parts of the light emitted by the quasars. The resulting spectrum consequently presents dark "valleys" that can be attributed to well-known elements.

If the fine-structure constant happens to change over the duration of the light's journey, the energy levels in the atoms would be affected and the wavelengths of the absorption lines would be shifted by different amounts. By comparing the relative gaps between the valleys with the laboratory values, it is possible to calculate alpha as a function of distance from us, that is, as a function of the age of the Universe.

These measures are however extremely delicate and require a very good modelling of the absorption lines. They also put exceedingly strong requirements on the quality of the astronomical spectra. They must have enough resolution to allow very precise measurement of minuscule shifts in the spectra. And a sufficient number of photons must be captured in order to provide a statistically unambiguous result.

For this, astronomers have to turn to the most advanced spectral instruments on the largest telescopes. This is where the Ultra-violet and Visible Echelle Spectrograph (UVES) and ESO's Kueyen 8.2-m telescope at the Paranal Observatory is unbeatable, thanks to the unequalled spectral quality and large collecting mirror area of this combination.

Constant or not?

A team of astronomers [1], led by Patrick Petitjean (Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris and Observatoire de Paris, France) and Raghunathan Srianand (IUCAA Pune, India) very carefully studied a homogeneous sample of 50 absorption systems observed with UVES and Kueyen along 18 distant quasars lines of sight. They recorded the spectra of quasars over a total of 34 nights to achieve the highest possible spectral resolution and the best signal-to-noise ratio. Sophisticated automatic procedures specially designed for this programme were applied.

In addition, the astronomers used extensive simulations to show that they can correctly model the line profiles to recover a possible variation of alpha.

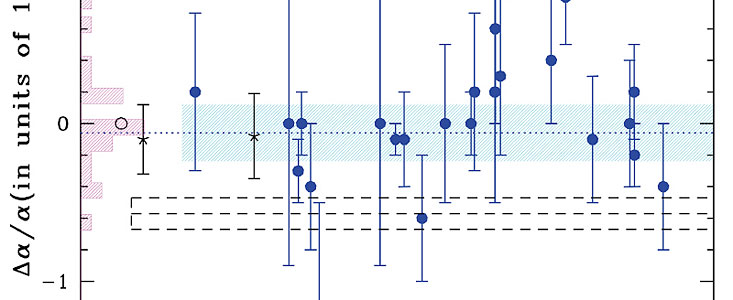

The result of this extensive study is that over the last 10,000 million years, the relative variation of alpha must be less than 0.6 part per million. This is the strongest constraint from quasar absorption lines studies to date. More importantly, this new result does not support previous claims of a statistically significant change of alpha with time.

Interestingly, this result is supported by another - less extensive - analysis, also conducted with the UVES spectrometer on the VLT [2]. Even though those observations were only concerned with one of the brightest known quasar HE 0515-4414, this independent study lends further support to the hypothesis of no variation of alpha.

Even though these new results represent a significant improvement in our knowledge of the possible (non-) variation of one of the fundamental physical constants, the present set of data would in principle still allow variations that are comparatively large compared to those resulting from the measurements from the Oklo natural reactor. Nevertheless, further progress in this field is expected with the new very-high-accuracy radial velocity spectrometer HARPS on ESO's 3.6-m telescope at the La Silla Observatory (Chile). This spectrograph works at the limit of modern technology and is mostly used to detect new planets around stars other than the Sun - it may provide an order of magnitude improvement on the determination of the variation of alpha.

Other fundamental constants can be probed using quasars. In particular, by studying the wavelengths of molecular hydrogen in the remote Universe, one can probe the variations of the ratio between the masses of the proton and the electron. The same team is now engaged in such a large survey with the Very Large Telescope that should lead to unprecedented constraints on this ratio.

Notes

[1] The team is composed of Hum Chand and Raghunathan Srianand (IUCAA Pune, India), Patrick Petitjean (Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris, CNRS, and LERMA, Observatoire de Paris, France) and Bastien Aracil (Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris, CNRS, France).

[2] This result has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics Letters : "Probing the variability of the fine-structure constant with the VLT/UVES" by Ralf Quast, Dieter Reimers (Hamburg Observatory, Germany), and Sergei A. Levshakov (Department of Theoretical Astrophysics, St. Petersburg, Russia).

More information

The research presented in this Press Release is based on papers published in Physical Review Letters ("Limits on the time variation of the electromagnetic fine-structure constant in the low energy limit from absorption lines in the spectra of distant quasars" by Raghunathan Srianand, Hum Chand, Patrick Petitjean, and Bastien Aracil) and in the leading European astronomy journal Astronomy & Astrophysics ("Probing the cosmological variation of the fine-structure constant: Results based on VLT-UVES sample" by Hum Chand, Raghunathan Srianand, Patrick Petitjean, and Bastien Aracil).

Contacts

Patrick Petitjean

Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris

Paris, France

Tel: +33-1-44328150

Email: petitjean@iap.fr

Raghunathan Srianand

Pune University Campus

Pune, India

Tel: 091-20-569 1414 (ext 320)

Email: anand@iucaa.ernet.in

About the Release

| Release No.: | eso0407 |

| Legacy ID: | PR 05/04 |

| Name: | Quasar |

| Type: | Unspecified : Cosmology |

| Facility: | Very Large Telescope |

| Instruments: | UVES |

| Science data: | 2004PhRvL..92l1302S 2004A&A...417..853C |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.