Pressemitteilung

Cosmological Gamma-Ray Bursts and Hypernovae Conclusively Linked

Clearest-Ever Evidence from VLT Spectra of Powerful Event

18. Juni 2003

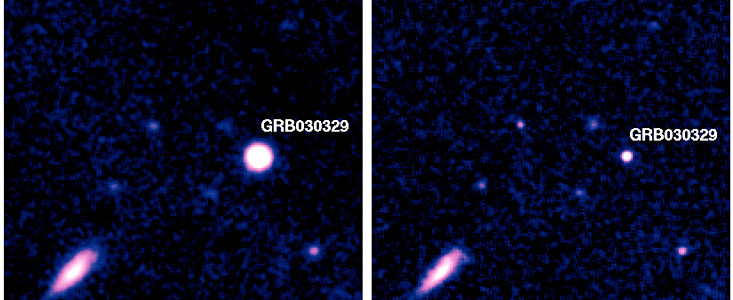

A very bright burst of gamma-rays was observed on March 29, 2003 by NASA's High Energy Transient Explorer (HETE-II) , in a sky region within the constellation Leo. Within 90 min, a new, very bright light source (the "optical afterglow") was detected in the same direction by means of a 40-inch telescope at the Siding Spring Observatory (Australia) and also in Japan. The gamma-ray burst was designated GRB 030329 , according to the date. And within 24 hours, a first, very detailed spectrum of this new object was obtained by the UVES high-dispersion spectrograph on the 8.2-m VLT KUEYEN telescope at the ESO Paranal Observatory (Chile). It allowed to determine the distance as about 2,650 million light-years (redshift 0.1685). Continued observations with the FORS1 and FORS2 multi-mode instruments on the VLT during the following month allowed an international team of astronomers [1] to document in unprecedented detail the changes in the spectrum of the optical afterglow of this gamma-ray burst . Their detailed report appears in the June 19 issue of the research journal "Nature". The spectra show the gradual and clear emergence of a supernova spectrum of the most energetic class known, a "hypernova" . This is caused by the explosion of a very heavy star - presumably over 25 times heavier than the Sun. The measured expansion velocity (in excess of 30,000 km/sec) and the total energy released were exceptionally high, even within the elect hypernova class. From a comparison with more nearby hypernovae, the astronomers are able to fix with good accuracy the moment of the stellar explosion. It turns out to be within an interval of plus/minus two days of the gamma-ray burst. This unique conclusion provides compelling evidence that the two events are directly connected. These observations therefore indicate a common physical process behind the hypernova explosion and the associated emission of strong gamma-ray radiation. The team concludes that it is likely to be due to the nearly instantaneous, non-symmetrical collapse of the inner region of a highly developed star (known as the "collapsar" model). The March 29 gamma-ray burst will pass into the annals of astrophysics as a rare "type-defining event", providing conclusive evidence of a direct link between cosmological gamma-ray bursts and explosions of very massive stars.

What are Gamma-Ray Bursts?

One of the currently most active fields of astrophysics is the study of the dramatic events known as "gamma-ray bursts (GRBs)" . They were first detected in the late 1960's by sensitive instruments on-board orbiting military satellites, launched for the surveillance and detection of nuclear tests. Originating, not on the Earth, but far out in space, these short flashes of energetic gamma-rays last from less than a second to several minutes.

Despite major observational efforts, it is only within the last six years that it has become possible to pinpoint with some accuracy the sites of some of these events. With the invaluable help of comparatively accurate positional observations of the associated X-ray emission by various X-ray satellite observatories since early 1997, astronomers have until now identified about fifty short-lived sources of optical light associated with GRBs (the "optical afterglows").

Most GRBs have been found to be situated at extremely large ("cosmological") distances. This implies that the energy released in a few seconds during such an event is larger than that of the Sun during its entire lifetime of more than 10,000 million years. The GRBs are indeed the most powerful events since the Big Bang known in the Universe.

During the past years circumstantial evidence has mounted that GRBs signal the collapse of massive stars. This was originally based on the probable association of one unusual gamma-ray burst with a supernova ("SN 1998bw", also discovered with ESO telescopes). More clues have surfaced since, including the association of GRBs with regions of massive star-formation in distant galaxies, tantalizing evidence of supernova-like light-curve "bumps" in the optical afterglows of some earlier bursts, and spectral signatures from freshly synthesized elements, observed by X-ray observatories.

VLT observations of GRB 030329

On March 29, 2003 (at exactly 11:37:14.67 hrs UT) NASA's High Energy Transient Explorer (HETE-II) detected a very bright gamma-ray burst. Following identification of the "optical afterglow" by a 40-inch telescope at the Siding Spring Observatory (Australia), the redshift of the burst [3] was determined as 0.1685 by means of a high-dispersion spectrum obtained with the UVES spectrograph at the 8.2-m VLT KUEYEN telescope at the ESO Paranal Observatory (Chile).

The corresponding distance is about 2,650 million light-years. This is the nearest normal GRB ever detected, therefore providing the long-awaited opportunity to test the many hypotheses and models which have been proposed since the discovery of the first GRBs in the late 1960's.

With this specific aim, the ESO-lead team of astronomers [1] now turned to two other powerful instruments at the ESO Very Large Telescope (VLT), the multi-mode FORS1 and FORS2 camera/spectrographs. Over a period of one month, until May 1, 2003, spectra of the fading object were obtained at regular rate, securing a unique set of observational data that documents the physical changes in the remote object in unsurpassed detail.

The hypernova connection

Based on a careful study of these spectra, the astronomers are now presenting their interpretation of the GRB 030329 event in a research paper appearing in the international journal "Nature" on Thursday, June 19. Under the prosaic title "A very energetic supernova associated with the gamma-ray burst of 29 March 2003", no less than 27 authors from 17 research institutes, headed by Danish astronomer Jens Hjorth conclude that there is now irrefutable evidence of a direct connection between the GRB and the "hypernova" explosion of a very massive, highly evolved star.

This is based on the gradual "emergence" with time of a supernova-type spectrum, revealing the extremely violent explosion of a star. With velocities well in excess of 30,000 km/sec (i.e., over 10% of the velocity of light), the ejected material is moving at record speed, testifying to the enormous power of the explosion.

Hypernovae are rare events and they are probably caused by explosion of stars of the so-called "Wolf-Rayet" type [4]. These WR-stars were originally formed with a mass above 25 solar masses and consisted mostly of hydrogen. Now in their WR-phase, having stripped themselves of their outer layers, they consist almost purely of helium, oxygen and heavier elements produced by intense nuclear burning during the preceding phase of their short life.

"We have been waiting for this one for a long, long time ", says Jens Hjorth, " this GRB really gave us the missing information. From these very detailed spectra, we can now confirm that this burst and probably other long gamma-ray bursts are created through the core collapse of massive stars. Most of the other leading theories are now unlikely."

A "type-defining event"

His colleague, ESO-astronomer Palle Møller, is equally content: "What really got us at first was the fact that we clearly detected the supernova signatures already in the first FORS-spectrum taken only four days after the GRB was first observed - we did not expect that at all. As we were getting more and more data, we realised that the spectral evolution was almost completely identical to that of the hypernova seen in 1998. The similarity of the two then allowed us to establish a very precise timing of the present supernova event."

The astronomers determined that the hypernova explosion (designated SN 2003dh [2]) documented in the VLT spectra and the GRB-event observed by HETE-II must have occurred at very nearly the same time. Subject to further refinement, there is at most a difference of 2 days, and there is therefore no doubt whatsoever, that the two are causally connected.

"Supernova 1998bw whetted our appetite, but it took 5 more years before we could confidently say, we found the smoking gun that nailed the association between GRBs and SNe" adds Chryssa Kouveliotou of NASA. "GRB 030329 may well turn out to be some kind of 'missing link' for GRBs."

In conclusion, GRB 030329 was a rare "type-defining" event that will be recorded as a watershed in high-energy astrophysics.

What really happened on March 29 (or 2,650 million years ago)?

Here is the complete story about GRB 030329, as the astronomers now read it.

Thousands of years prior to this explosion, a very massive star, running out of hydrogen fuel, let loose much of its outer envelope, transforming itself into a bluish Wolf-Rayet star [3]. The remains of the star contained about 10 solar masses worth of helium, oxygen and heavier elements.

In the years before the explosion, the Wolf-Rayet star rapidly depleted its remaining fuel. At some moment, this suddenly triggered the hypernova/gamma-ray burst event. The core collapsed, without the outer part of the star knowing. A black hole formed inside, surrounded by a disk of accreting matter. Within a few seconds, a jet of matter was launched away from that black hole.

The jet passed through the outer shell of the star and, in conjunction with vigorous winds of newly formed radioactive nickel-56 blowing off the disk inside, shattered the star. This shattering, the hypernova, shines brightly because of the presence of nickel. Meanwhile, the jet plowed into material in the vicinity of the star, and created the gamma-ray burst which was recorded some 2,650 million years later by the astronomers on Earth. The detailed mechanism for the production of gamma rays is still a matter of debate but it is either linked to interactions between the jet and matter previously ejected from the star, or to internal collisions inside the jet itself.

This scenario represents the "collapsar" model, introduced by American astronomer Stan Woosley (University of California, Santa Cruz) in 1993 and a member of the current team, and best explains the observations of GRB 030329.

"This does not mean that the gamma-ray burst mystery is now solved", says Woosley . "We are confident now that long bursts involve a core collapse and a hypernova, likely creating a black hole. We have convinced most skeptics. We cannot reach any conclusion yet, however, on what causes the short gamma-ray bursts, those under two seconds long."

Endnoten

[1]: Members of the Gamma-Ray Burst Afterglow Collaboration at ESO (GRACE) team include Jens Hjorth, Páll Jakobsson, Holger Pedersen, Kristian Pedersen andDarach Watson (Astronomical Observatory, NBIfAFG, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), Jesper Sollerman (Stockholm Observatory, Sweden), Palle Møller (ESO-Garching, Germany), Johan Fynbo (Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Aarhus, Denmark), Stan Woosley (Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz, USA), Chryssa Kouveliotou (NSSTC, Huntsville, Alabama, USA), Nial Tanvir (Department of Physical Sciences, University of Hertfordshire, UK), Jochen Greiner (Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Garching, Germany), Michael Andersen (Astrophysikalisches Institut, Potsdam, Germany), Alberto Castro-Tirado(Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, Granada, Spain), José María Castro Cerón, Andy Fruchter, Javier Gorosabel and James Rhoads (Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Maryland, USA), Lex Kaper, Evert Rol, Ed van den Heuvel and Ralph Wijers (Astronomical Institute Anton Pannekoek, Amsterdam, Netherlands), Sylvio Klose(Thüringer Landessternwarte Tautenburg, Germany), Nicola Masetti and Eliana Palazzi (Istituto di Astrofisica Spaziale e Fisica Cosmica - Sezione di Bologna, CNR, Italy),Elena Pian (INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste, Italy) and Paul Vreeswijk (ESO-Santiago, Chile)

[2]: See Circular 8114 of the International Astronomical Union, issued on April 9, 2003.

[3]: In astronomy, the "redshift" denotes the fraction by which the lines in the spectrum of an object are shifted towards longer wavelengths. Since the redshift of a cosmological object increases with distance, the observed redshift of a remote galaxy also provides an estimate of its distance.

[4]: Wolf-Rayet stars are named after two 19th-century French astronomers, Charles Wolf and Georges Rayet .

Kontaktinformationen

Jens Hjorth

Astronomical Observatory, NBIfAFG

Copenhagen, Denmark

Tel: +45 3532 5928

E-Mail: jens@astro.ku.dk

Chryssa Kouveliotou

NSSTC

Huntsville, Alabama, USA

Tel: +1 256 961 7604

E-Mail: Chryssa.Kouveliotou-1@nasa.gov

Palle Møller

ESO

Garching, Germany

Tel: +49 89 3200-6246

E-Mail: pmoller@eso.org

Jesper Sollerman

Stockholm Observatory

Stolkholm, Sweden

Tel: +46 8 55378554

E-Mail: jesper@astro.su.se

Über die Pressemitteilung

| Pressemitteilung Nr.: | eso0318 |

| Legacy ID: | PR 16/03 |

| Name: | GRB 030329 |

| Typ: | Early Universe : Cosmology : Phenomenon : Gamma Ray Burst |

| Facility: | Very Large Telescope |

| Instruments: | FORS1, FORS2 |

| Science data: | 2003Natur.423..847H |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.